Melqart in Leiden

Right now, the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden (which is, to my good fortune, located just a stone’s throw from where I live!) is hosting an exhibition on ancient Carthage. There’s certainly things that I would have done differently if I had been in charge, but it’s an interesting exhibition nevertheless, especially because it present a wide range of Carthaginian objects from a number of museums in Tunisia and elsewhere.

Carthage was founded as a Phoenician colony in what is now Tunisia in the ninth century BC. It was in ideal position for trade in the Mediterranean and slowly became more prosperous, developing into an empire. The Carthaginians expanded their sphere of influence and founded cities elsewhere, most notably on the nearby island of Sicily, where they came into conflict with the Greeks who had also been founding cities there (no doubt at least partially to the chagrin of the local population). You can read Ancient Warfare issue VII.2 for more details on the struggles between the Greeks and Carthaginians over Sicily.

Carthage was founded as a Phoenician colony in what is now Tunisia in the ninth century BC. It was in ideal position for trade in the Mediterranean and slowly became more prosperous, developing into an empire. The Carthaginians expanded their sphere of influence and founded cities elsewhere, most notably on the nearby island of Sicily, where they came into conflict with the Greeks who had also been founding cities there (no doubt at least partially to the chagrin of the local population). You can read Ancient Warfare issue VII.2 for more details on the struggles between the Greeks and Carthaginians over Sicily.

The Carthaginians obviously shared many similarities with their Phoenician ancestors, not in the least their art. Phoenician and, by extension, Carthaginian art is a curious mix of different influences, most notably Egyptian and Mesopotamian (Assyrian and Babylion), though not seldom the art is, compared to their sources of inspiration, a little crude.

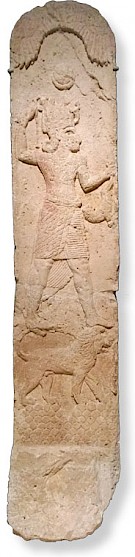

A curious object in this exhibition on Carthage is the beautiful stela depicted on this page. It comes not from Carthage, but from Amrit, a town located between the Phoenician cities of Arvad and Tripoli; the modern site is located in what is today the very south of Syria. It is made from limestone and dates to ca. 550 BC.

The figure depicted on the stela is Melqart, an important divinity among the Phoenicians and also worshipped among the Carthaginians. The Phoenicians generally built a temple to Melqart in each of their colonies, and Carthage was no exception. Some Carthaginian names also incorporate elements of Melqart’s name, such as Hamilcar. (By comparison, the -bal part in a name like Hannibal refers to Baal Hammon, one of the chief deities among the Phoenicians and Carthaginians, as well as the father of Melqart.)

On the stela, Melqart is shown standing on top of a male lion, a symbol of strength and power as well as royalty. The lion was also a symbol of the untamed wilds that existed outside of civilization, and in Near-Eastern art we regularly encounter scenes in which kings hunt lions, which symbolized the ruler’s ability to establish law and order over chaos. The fact that Melqart is shown standing on top of the lion should probably be interpreted in the same way.

The style of the lion resembles Assyrian reliefs. But note the Egyptian influences as far as the position of Melqart is concerned; the crown on his head also evokes Egyptian headdress typical of pharaohs. The sun disk on top of his head, as well as the wings at the top of the stele (another element common in the art of the ancient Near East), are again references to the world of gods.

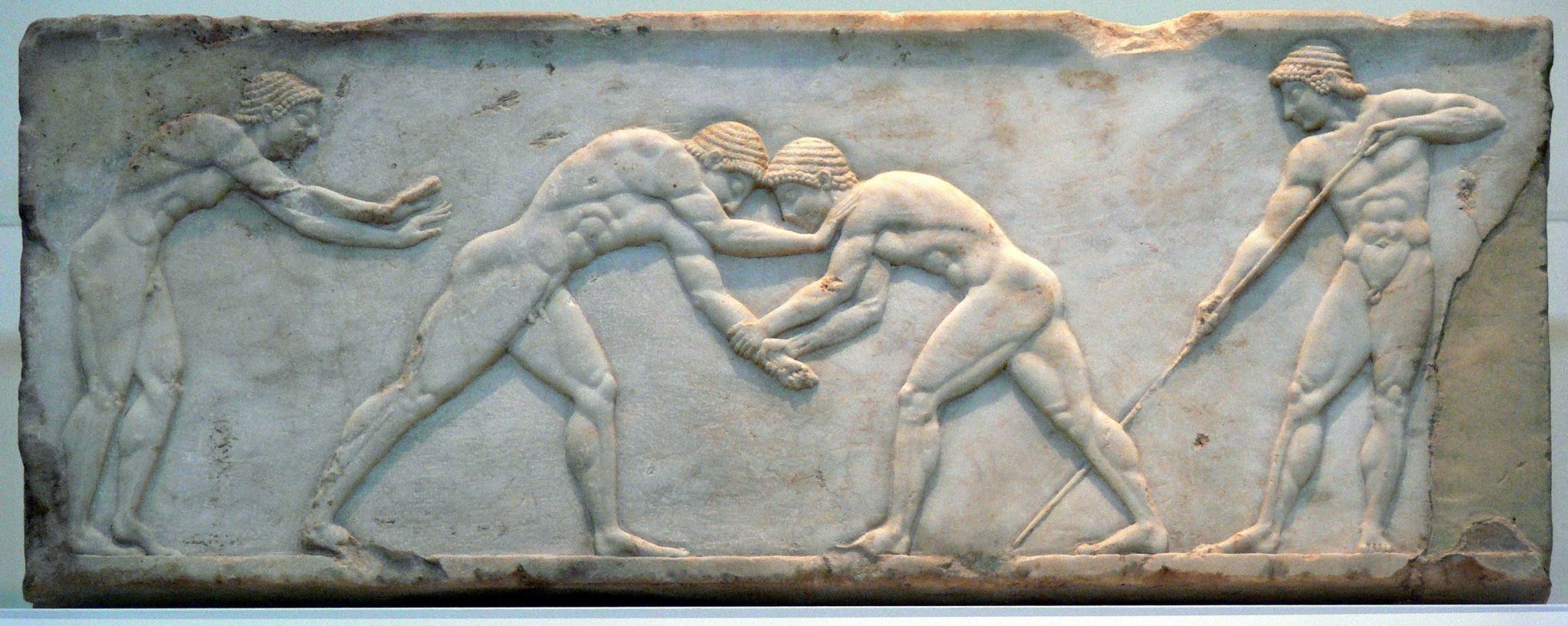

The later Greeks and Romans equated Melqart with our good friend Heracles, as his deeds were thought to be similar. Melqart was also associated with a rite involving a funeral pyre, evoking the death (and apotheosis) of Heracles. Over the course of the Hellenistic and early Roman imperial periods, Melqart was increasingly depicted in the fashion of Heracles himself, complete with club and lion skin.