Time, part 4: the date of Easter

In the first article of this series, I wrote about the quest for a good calendar, and I mentioned the Babylonian version: a cycle of nineteen years, in which the third, sixth, eighth, eleventh, fourteenth, seventeenth, and last year get an additional, thirteenth month. In other words, it is a cycle of 19x12 + 7 = 235 months, which are indeed – give or take a few hours – identical to nineteen years. New Year’s day will always be the New Moon closest to the beginning of the spring.

In the first article of this series, I wrote about the quest for a good calendar, and I mentioned the Babylonian version: a cycle of nineteen years, in which the third, sixth, eighth, eleventh, fourteenth, seventeenth, and last year get an additional, thirteenth month. In other words, it is a cycle of 19x12 + 7 = 235 months, which are indeed – give or take a few hours – identical to nineteen years. New Year’s day will always be the New Moon closest to the beginning of the spring.

Because the Babylonian cycle, which is also known as the Cycle of Meton, is nearly faultless, it was adapted by several other nations, including the Jews. The document known as Some Works of the Law, which is probably a letter to the high priest Jonathan (r.150–143 BC), seems to be a response to the adoption of a foreign calendar: the author tries to persuade the addressee that there are better calendars. The high priest was not convinced, however, and the Jews use the Babylonian calendar until this very day.

It is this calendar that Jesus used when he went up to Jerusalem to celebrate Passover, which started on the afternoon of 14 Nisan (the “preparation day”), when the paschal lamb was sacrificed. It was eaten during the evening, which, according to Jewish time reckoning, belongs to the next day, 15 Nisan. This was always a full moon. According to the gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke, the Last Supper was a Passover meal, and Jesus’ arrest, his trial, and execution all took place during a fifteenth of Nisan.

The gospel of John, on the other hand, says that it was the preparation day, 14 Nisan, which makes the Last Supper an ordinary meal, while Jesus died at the very moment that the priests sacrificed the paschal lamb. In other words, the four gospels have different ways to connect Jesus’ death to Passover: while John presents Christ as the lamb of God, the other evangelists present Jesus as a pious Jew eating the Passover meal. Theologically, there is not much difference: the connection between Jesus’ death and Passover is agreed upon.

Besides, for Christians, the date of Jesus’ death is of less importance than the day of his resurrection. The early Church celebrated this (and continues to celebrate it) on the first Sunday after Jewish Passover – in other words: Easter falls on the first Sunday after the first full moon after the beginning of spring.

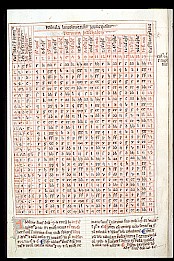

However, for a long time, there were Christians who preferred to worship on 14 Nisan. The debate about the precise date, which was also a debate about how Jewish Christianity wanted to be, has lasted for centuries. One of the results was that it was expected that bishops could calculate the correct, orthodox Easter date (the “computus”). To facilitate this, the Christian era was created – something for which we may be grateful. After all, the alternative might have been that we would still be counting regnal years or naming our years after magistrates.