Time, part 6: the sundial of Augustus

In an earlier blog post in this series, I wrote about water clocks, which were used to track the passage of time, especially during the night and for specific purposes, such as making sure lawyers stayed within their allotted time to talk. But the ancients also used another device to mark the hours during the day, namely the sundial.

In an earlier blog post in this series, I wrote about water clocks, which were used to track the passage of time, especially during the night and for specific purposes, such as making sure lawyers stayed within their allotted time to talk. But the ancients also used another device to mark the hours during the day, namely the sundial.

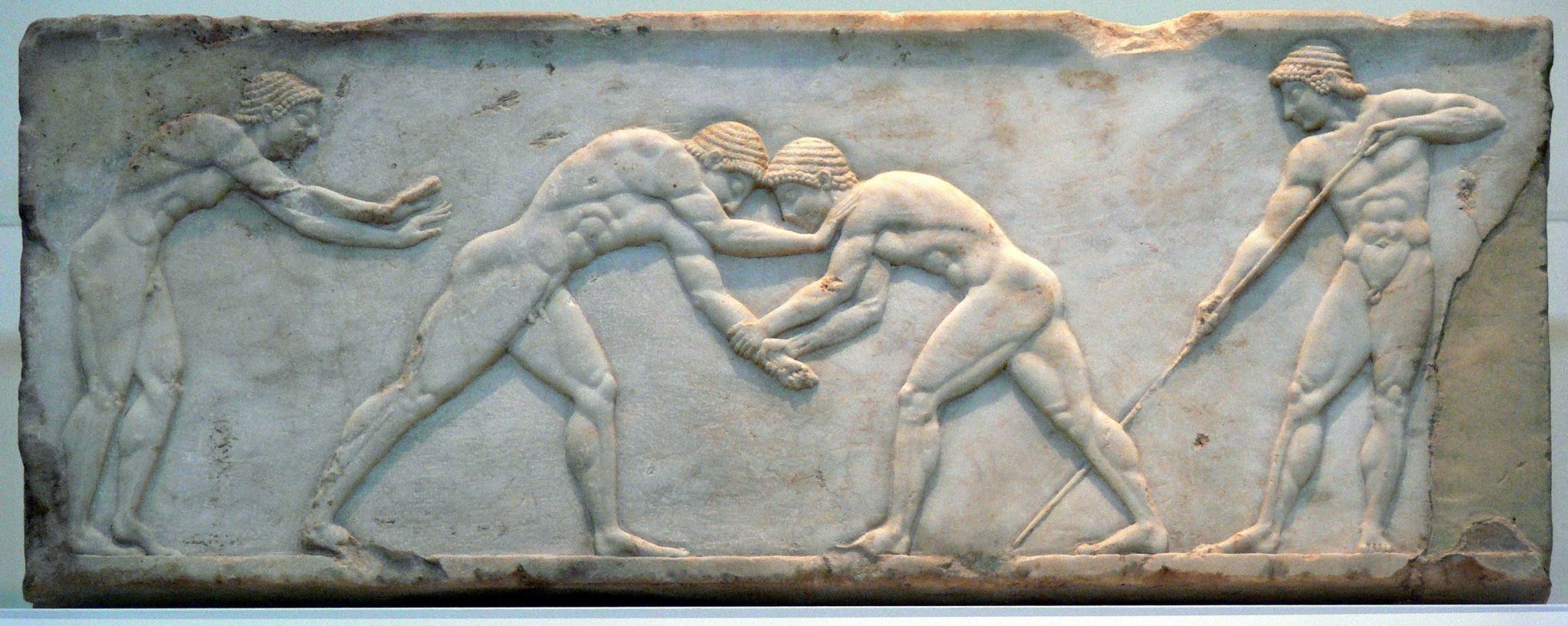

The ancestor of the sundial was the so-called shadow clock, a simple device where a cross bar’s shadow marked the time as the sun traversed across the sky during the day. The earliest evidence for a shadow clock are, again, found in a tomb in Egypt, dating to around 1300 BC. Sundials, with a vertical indicator or gnomon (often of stone) used to mark the hour as its shadow fell across lines arranged in a more or less semi-circular shape, were developed and perfected by the Romans.

One of the most remarkable sundials is the so-called Horologium of the Roman Emperor Augustus (r. 27 BC–AD 14), also referred to as the Horologium Augusti or Solarium Augusti. This gigantic sundial was located in the Campus Martius, not far from the famous Ara Pacis Augustae (Augustus’ monumental ‘Altar of Peace’). It was built in 10 BC and dedicated to Apollo, who by Roman times had come to be regarded as a god of the sun and who was also Augustus’ patron deity.

Interestingly, the gnomon was an Egyptian obelisk that Augustus had carried off from Heliopolis after the subjugation of Egypt. Napoleon, inspired by this action, would later also loot an ancient obelisk from Egypt to mark the conclusion of his expedition into Egypt.

A large number of lines had been engraved into the pavement to one side of the obelisk so that the shadow cast by the sun would highlight the particular hour of the day as it rose and set. The entire square thus served as a dial plate. Inscriptions indicated the zodiacal signs and also provided other details that would be of interest to visitors of the monument.

The monuments on the Campus Marius were carefully arranged in such a fashion that on the day of Augustus’ birth the shadow cast by the obelisk pointed directly to the doorway of the Ara Pacis. In this way, visitors were reminded of what the reign of Augustus had brought them: reliefs on the walls surrounding the actual altar (many of which have been heavily reconstructed during the regime of Mussolini) reinforced the notion of how the first Roman emperor had given the realm peace and prosperity.

As such, the sundial doesn’t betray any kind of interest in the passage of time that fits our modern obsession with clocks. Augustus’ sundial was a deliberate piece of political propaganda, which highlighted the beginning of a new era of prosperity brought on by the rise to power of Augustus himself. Indeed, in 17 BC, Augustus commissioned a new hymn, composed by Horace, the Carmen Saeculare, which celebrated the end of one era and the start of a new, and which emphasized the importance of Augustus’ patron deity, Apollo.

Further reading

- Peter James and Nick Thorpe, Ancient Inventions (1994).

- Nancy H. Ramage and Andrew Ramage, Roman Art (second edition, 1995).

Picture credit: photo of the obelisk by Matthias Kabel, from Wikimedia Commons.