The Autumn of Perseus

As a follow-up to last year’s ‘Summer of Hercules’, I am pleased to announce that this will be the ‘Autumn of Perseus’. For the next few weeks, I will post blog articles on a variety of matters concerning this Greek hero. You can expect blog posts on ancient art featuring Perseus, the Clash of the Titans movies (all three of them), comic books based on the stories about this hero, a review of a monograph by Daniel Ogden, and more.

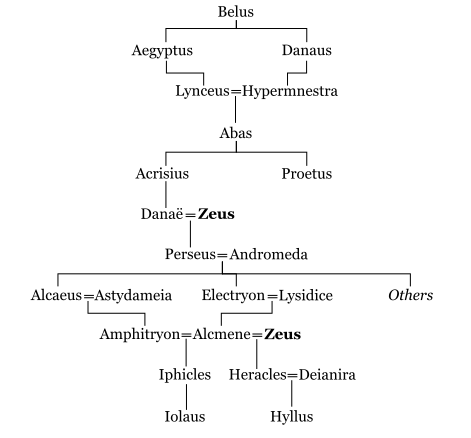

Perseus was Heracles’ great-grandfather and, like Heracles, he was a son of Zeus and therefore a demigod. For convenience, I have made a family tree so that you can more easily understand where Perseus came from and how Heracles is related to him:

Perseus is often considered the archetypical Greek hero and generally regarded as one of the earliest of the Greek heroes, if not the earliest hero. Like all early heroes, such as Bellerophon and Heracles, he made his name primarily as a monster-slayer. His story can be pieced together from disparate sources (e.g. Homer, Hesiod, the Ehoiai, poems by Pindar, and so forth), but a convenient summary is provided in the Bibliotheca of Pseudo-Apollodorus, book 2.4 and further (which you read on the Theoi website).

The story of Perseus

Briefly, the story of Perseus is as follows. Acrisius, king of Argos, was told by the Oracle of Delphi that his grandson would slay him. He therefore locked his daughter, Danaë, away so that she couldn’t get pregnant. However, Zeus – randy as always – fell in love with the beautiful girl, found a way inside her cell, and fathered a child, Perseus. Angered, Acrisius put his daughter and her child in a chest and cast it into the sea.

However, the gods ensured that the chest arrived safely at the island of Seriphos. Here, a man named Dictys offered shelter to Danaë and decided to raise the boy as his own. Polydectes, Dictys’ brother and king of the island, fell in love with Danaë, but by that time Perseus had fully grown and he was fearful of him. He then pretended to want to marry a certain Hippodamia and asked all he knew to send gifts to him. The required gifts were horses, according to Pseudo-Apollodorus, but Perseus had no horses to give. When Perseus told Polydectes that he would give him anything if he could, including the head of a gorgon, the king leapt at the chance and told him that, indeed, Perseus should bring him just that.

There is quite a bit of confusion about this part of the story. Pseudo-Apollodorus offers a convenient summary, but other versions of the story claim that Dictys was just a fisherman (which would explain the difficulty in obtaining horses), and that when asked to give Polydectes a horse Perseus exclaimed, ‘The head of a gorgon!’, which probably meant, ‘It’s impossible!’

Regardless, Perseus – being a true hero and of divine blood – agreed to fetch the head of a gorgon. The gods favoured him, and Hermes and Athena in particular, who were Perseus’ half-brother and half-sister, assisted him. He first had to go to the Graeae, three witches who shared one tooth and one eye between them and who were the only ones who knew where to find the gorgons. Perseus snatched their tooth and eye and said he would return them only if the women told him where to find the gorgons. (According to Pseudo-Apollodorus, they also gave him winged sandals, the helmet of Hades that turns the wearer invisible, and a satchel to put the head of the gorgon in; other sources say that the gods gave him what he needed.)

Perseus soon reached the land of the gorgons. These monsters were also three sisters: two were immortal, but one was mortal. The latter was Medusa. It was said that whoever looked at the face of a gorgon would turn into stone, so Perseus approached them by looking at them in the reflection of the shiny shield given to him by Athena. Perseus approached the three while they were sleeping and cut off Medusa’s head. From the wound sprouted Pegasus, the winged horse, and the hero Chrysaor, wielding a flaming sword. He stuffed it into his satchel and fled, pursued by Medusa’s sisters. But the sisters lost track of Perseus, thanks to the helmet that allowed him to turn invisible.

On his way back to Seriphos, he came across Ethiopia (or otherwise Joppa, a place on the Levantine coast, according to others), where he saw that Andromeda, the king’s daughter, had been chained to a rock and left out to feed a sea monster. The monster was sent by Poseidon after Andromeda’s mother, Cassiopeia, claimed to be better and prettier than the Nereids, nymphs of the sea. The monster could only be appeased if Andromeda was left as a sacrifice. Perseus fell in love with her and after asking her parents for her hand in marriage, he fought and slew the sea-monster.

Perseus and Andromeda lingered in her homeland for a while before returning to Seriphos. There, Perseus discovered that Dictys and Danaë had taken refuge in a sanctuary as Polydectes had tried to seize the woman by force. Perseus went to Polydectes and his friends and used the head of Medusa to turn them into stone. He then made Dictys king of Seriphos and returned his quest items to the gods. He also gave Athena the head of the gorgon, which she then fixed on her aegis, the goat-skin she usually has wrapped around her shoulders and that was a gift from Zeus. (Alternatively, she fixed the head to the middle of her shield.)

Perseus then travelled to Argos to meet his grandfather, Acrisius, whom he wanted to forgive. However, when Acrisius learnt that Perseus was on his way, he fled and left for Larissa. There, the king was holding funeral games and Perseus had, by coincidence, decided to take part in the games. He threw a discus so far that it landed into the audience. As fate would have it, Acrisius was watching the games and got hit in the head by the discus and died. (In Greek myths, the Oracle’s prophesies always come true.)

Ashamed of having accidentally killed Acrisius, Perseus renounced the throne of Argos and instead swapped it for Tiryns with his cousin, Megapenthes (son of Proetus). Pseudo-Apollodorus says that Perseus also ‘fortified’ Midea and Mycenae; in other versions of the story, he actually founded these cities.