A Chinese Invasion of Korea in 645

China and Korea have a long history with each other - often involving conflict, but also with trade and cultural exchange. This is reflected in Korea’s oldest surviving chronicle - the Samguk Sagi.

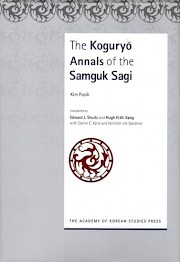

During the reign of King Injong (r. 1122-1146), an order was sent to the government official Kim Busik to compile the history of Korea’s Three Kingdoms period (57 BC to 668 AD). His work, known as the Samguk Sagi, was created in the style of Chinese historiography and made extensive use of Chinese sources.

The invasion of the Korean kingdom of Koguryŏ in the year 645 is mostly told from the Chinese point of view. The Tang Dynasty Emperor Taizong (r. 626-649) led the military campaign into what is now North Korea, with over 100,000 troops attacking by land and sea. The first few weeks of the campaign went well for the Chinese, as several fortresses quickly fell and a Korean army was routed in battle. However, once they reached Ansi Fortress on July 18, 645, they found the Koguryŏ defenders putting up a stiff resistance.

The siege dragged on for several weeks, and one day Emperor Taizong heard the sounds of chickens and pigs coming from within the fortress. He went to one of his generals and told him:

‘’We have been laying siege to this fortress for a long time and the smoke rising within the fortress grows lesser day by day. That the sounds of the pigs and fowl have now suddenly grown so loud must mean to feast the soldiers so that at night they may go out to raid us. Rigorously prepare the troops for this.”

As the Emperor predicted, several hundred Koguryŏ troops climbed down from the fortress, but were quickly defeated by the Chinese. The siege of Ansi continued, with the Samguk Sagi relating that:

Daozong, Prince of Jiangxia, directed people to pile up an earthen mound at the southeast corner of the fortress in order to bring more pressure to bear. Within the fortress as well efforts were undertaken to build the walls higher to foil this strategy. The troops were divided into several groups, fighting six or seven shifts in day. Whenever war chariots and catapults were employed to pull down the parapets, the defenders erected wooden scaffolds to bridge the gap. As Daozong was wounded in his foot, the Emperor personally treated him with acupuncture. The effort to pile up the wall went on day and night without cease for sixty days employing the labor of five thousand men. Only about twenty or thirty ch’ok (7 to 11 metres) separated the earthen mound’s summit from the fortress wall so that from the top one could come down into fortress interior.

When it seemed that the Chinese forces were about to make a breakthrough, a sudden turn of events took place - part of the earthen mountain collapsed, and the Korean soldiers were able to take advantage of the chaotic situation to charge out of their fortress and capture the mound. This would ruin the plans of the Emperor, and the autumn weather would arrive before another plan could be enacted. The Samguk Sagi explains:

Because the cold came early to the Liaodong region, the grass dried up and water began to freeze, it was difficult to maintain soldiers and horses for long and, what is more, provisions all but ran out, so the Emperor gave orders to withdraw. First he selected the households of Liao and Gai prefectures to cross over the Liao River to China, and then rallied Tang troops below Ansi Fortress to return to China. Those in the fortress made no move to go out and only the fortress commander mounted the heights of the fortress and there made a bow of farewell. The Emperor, appreciating this commander’s steadfast defense of the fortress, left him a hundred bolts of silk in recognition of his service to his Lord.

The retreat began on October 13th, with the Chinese forces taking with them 70,000 civilians. Winter winds and snow would cause many of the invaders to perish, and Korea was safe for the time being. Tang Emperor Taizong would make at least two more attempts to conquer Koguryŏ before he died in the year 649. Kim Pusik, the author of the Samguk Sagi added some commentary to the episode, writing that the Chinese ruler was:

in his use of military tactics his singular use of strategy knew no bounds and in every engagement he was unequalled. Yet in the battles of the Eastern Expedition, his defeat at Ansi Fortress really makes the fortress chief heroic and exceptional. However, his name has not been passed down to us in the histories…this is truly lamentable.

Other later works from Korea do reveal the name of the commander who defended Ansi Fortress - Yang Manch’un - with one chronicler adding that he personal shot an arrow at the Emperor which hit him in the eye.

Other later works from Korea do reveal the name of the commander who defended Ansi Fortress - Yang Manch’un - with one chronicler adding that he personal shot an arrow at the Emperor which hit him in the eye.

The Koguryo Annals of the Samguk Sagi, translated by Edward J. Shultz and Hugh H.W. Kang, was published in 2011 by the Academy of Korean Studies Press.

You can read more about medieval Korea and China in the latest issue of Medieval Warfare magazine.