The Battle of Hastings according to Geoffrey Gaimar

The Norman Conquest of England was a widely reported event, with several chroniclers and one fascinating tapestry offering accounts of how Duke William of Normandy defeated King Harold Godwineson at the Battle of Hastings on October 14, 1066. One source that has received little attention from historians is Estoire des Engleis - History of the English - by Geoffrey Gaimar. However, this writer offers some interesting details about the battle.

Gaimar was an Anglo-Norman scholar and poet who lived in the first half of the twelfth-century. We only know him from his work Estoire des Engleis, which is poetic version of the history of England from ancient times up to reign of William II. Perhaps because he wrote his history in the form of a poem, or because it was in French, historians have rarely made use of it.

Estoire des Engleis does offer a lengthy account of the events of 1066, starting with the death of King Edward the Confessor and the sight of a comet appearing in the night sky. Gaimar then goes on to explain the first invasion of England - the one led by King Harald Hardrada and Earl Tostig - which ended with King Harold’s victory at the Battle of Stamford Bridge.

The account then quickly moves to the Norman invasion of England, with Gaimar reporting that 11,000 French ships had crossed the English Channel and landed at Hastings. Once King Harold learns of their arrival he leaves northern England to deal with the new invaders. The author notes the Anglo-Saxon ruler “had great difficulty in bringing together a sufficient quantity because of the large number of losses he had sustained in the victory which God had granted him over the Norsemen.” Taking what troops he could, King Harold was joined by his brothers and Gurth and Leofwine and went to meet Duke William in battle.

Geoffrey Gaimar now begins in his account of the Battle of Hastings:

When the battle lines were drawn up and ready to engage, the numbers on both side were high, and their eagerness for combat made them seem like leopards. Then one of the French came riding out at speed in front of the others. His name was Taillefer, a minstrel-juggler of considerable courage, who was armed and mounted on a fine horse - an intrepid and noble warrior. Placing himself in front of the others, he performed amazing feats before the English: he seized his spear by the butt just as it if had been a little stick, threw it high up into the air and caught it again by its point as it fell. Three times he tossed the spear in this way, and by the time he raised it for a fourth time, he had come so close that he hurled it straight into the English [lines], and wounded one of the English troops as it drove into his body. He then stepped back, drew his sword, threw it high into the air and caught it again as it fell. People who saw him do this said to each other that the feats he was performing before their eyes were nothing short of magic.

The story of Taillefer has been mentioned by at least four other contemporary accounts, but none of them completely agree with the others on what exactly he did. Gaimar has this Norman minstrel slicing off the hand of another English soldier before being killed in a hail of thrown spears. With this opening show over, the main fighting begins with the Normans attacking the English:

A tremendous shouting broke out, and blows continued to be dealt and spears to be hurled right up until nightfall. Many a knight met a death there; I do not dare tell a lie and cannot put names to those who dealt the finest blows.

Gaimar’s account then diverges a little as he begins to talk about the exploits of Count Alan Rufus of Brittany, and how it would earn him rewards from Duke WIlliam. After a few lines about the Count, the narrative returns to the fighting:

Count Alan and the others fought so well that they were clear victors in the battle, and I can tell you that the English ended up the losers. At dusk falls, they take flight, leaving many a body behind bereft of its soul. Among those remaining was Harold’s and those of his two brothers. Because of them sons and fathers died, uncles and nephews also, men of every noble line. The English paid dearly for their outrageous behaviour.

Gaimar ends his account of the year 1066 by telling his readers that William was now the ruler of England, and that “he remained lord of it for twenty-two years, give or take five weeks.”

You can read the full version of Gaimar’s work - Estoire des Engleis - History of the English - which has been edited and translated by Ian Short and is published by Oxford University Press.

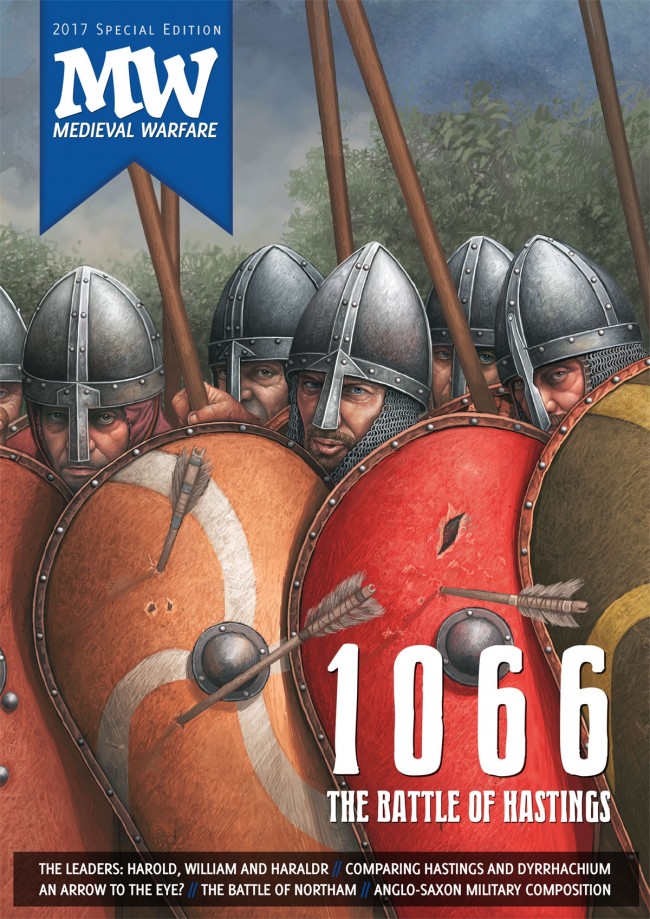

To learn more about the Battle of Hastings, take a look at our special issue of Medieval Warfare.