The commander's black steed

The life and death of Swiss reformer Huldrych Zwingli is covered in Medieval Warfare magazine III-2 as a special case of that issue’s theme ‘Warrior bishops of the Middle Ages’. Zwingli was only one of 25 church men to die at the Battle of Kappel on 11 October 1531. Another was Konrad Schmid (1476-1531) (linked page in German), a Swiss reformer and the last commander of the Küsnacht Commandery (linked page in German) of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem/Knights Hospitaller on Lake Zurich, Switzerland; thus a true man of the word and the sword.

The commander

Having completed his theological studies in Basel in 1516 at the advanced age of forty, Konrad Schmid became the last commander of the Küsnacht Commandery of the Order of Saint John of Jerusalem/Knights Hospitaller in 1519 (The Knights celebrate the 900th anniversary of its official Pontifical recognition in 2013). Küsnacht, now part of Zurich’s Goldcoast, was a small village situated on Lake Zurich.

Schmid vigorously participated in the discussions and debates of the Swiss reformation, usually as a calming voice, especially against iconoclasm. He admonished Zwingli to watch his language and refrain from repeating harsh words such as that “mass was a work of the devil, the devil had devised monks and orders” (“die messe sei vom tüfel, der tüfel hätt die mönche und orden erdacht.”). Schmid, however, was vociferous in his condemnation of the Swiss Anabaptists whose intransigence threatened the survival of the reforms. Anabaptist Balthasar Hubmaier, burned at the stake by the Catholic authorities in Vienna on 10 March 1528, wrote ”The Johannite priest, Commander at Küsnacht was one of those most to blame for the severity of the government measures against the Anabaptists.”

Schmid vigorously participated in the discussions and debates of the Swiss reformation, usually as a calming voice, especially against iconoclasm. He admonished Zwingli to watch his language and refrain from repeating harsh words such as that “mass was a work of the devil, the devil had devised monks and orders” (“die messe sei vom tüfel, der tüfel hätt die mönche und orden erdacht.”). Schmid, however, was vociferous in his condemnation of the Swiss Anabaptists whose intransigence threatened the survival of the reforms. Anabaptist Balthasar Hubmaier, burned at the stake by the Catholic authorities in Vienna on 10 March 1528, wrote ”The Johannite priest, Commander at Küsnacht was one of those most to blame for the severity of the government measures against the Anabaptists.”

In 1529 and 1531, during both Kappel wars, Schmid served as chaplain. Together with Huldrych Zwingli and twenty-four other church leaders, he was killed at the battle of Kappel on 11 October 1531. Swiss poet Conrad Ferdinand Meyer (1825-1898) wrote a ballad about Schmid’s death, centering the action on his horse. C.F. Meyer is famous for his stirring narrative ballads. His most famous work Die Füße im Feuer (‘The Feet in the Fire’) uses the plight of French Hugennots during the French Wars of Religion to discuss the agony of how to act in a Christian manner faced with torturers.

In Der Rappe des Komtur (‘The Commander’s Black Steed’), C.F. Meyer pays tribute to loyalty. Loyalty is displayed first by the comradeship of two men who both died during the same battle, Huldrych Zwingli and Konrad Schmid, and secondly by the horse’s loyalty to its rider. The task the horse accomplished would have been a superb biathlon. A third time, loyalty is displayed by the people of Küsnacht towards their dead commander and his horse. The ballad is based on a local legend. Meyer added the wounding of the horse as well as its colour.

The journey of the horse

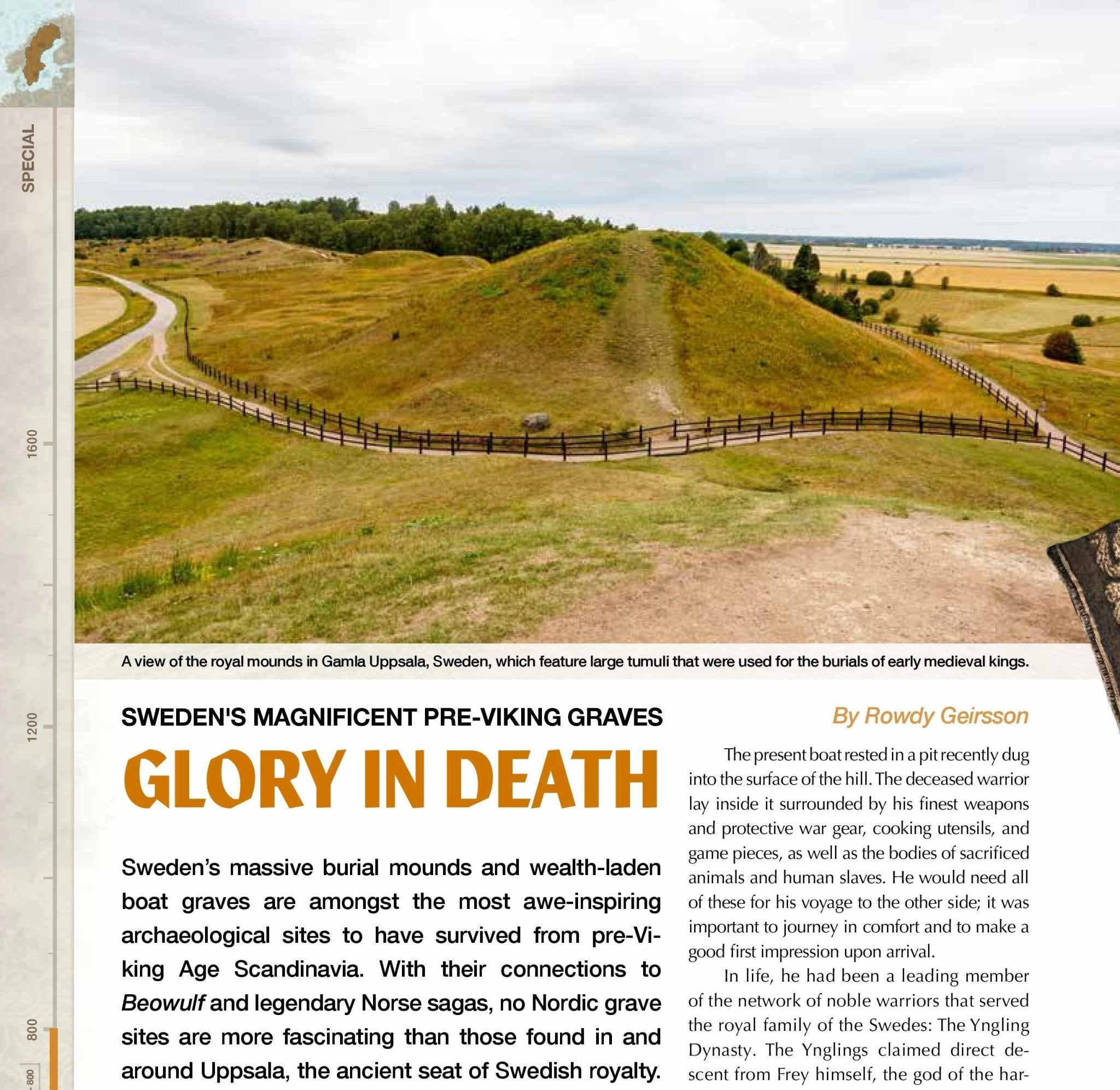

As the ballad states, men and horse started out on their journey from Küsnacht (413 meters above seal level) at dawn on 11 October 1531, crossing Lake Zurich in a barge. Then they will have marched 20 kilometers over the Albis chain of hills (600-900 m above sea level) to arrive at Kappel (573 m above sea level).

Schmid would probably not have ridden his war horse, but a second horse. The contingent from Küsnacht would have joined the main force from Zurich and arrived at Kappel at around 3 pm to rest and get into formation. The battle started around 4 to 5 pm, and was over all too quickly. In contrast to the ballad in which the horse receives a wound, at the actual battle Schmid would have fought dismounted as was customary in the infantry-dominant Swiss armies. The large number of leaders slain (both religious and political) is a testament both to their bravery as well as a lack of a get-away horse.

Schmid would probably not have ridden his war horse, but a second horse. The contingent from Küsnacht would have joined the main force from Zurich and arrived at Kappel at around 3 pm to rest and get into formation. The battle started around 4 to 5 pm, and was over all too quickly. In contrast to the ballad in which the horse receives a wound, at the actual battle Schmid would have fought dismounted as was customary in the infantry-dominant Swiss armies. The large number of leaders slain (both religious and political) is a testament both to their bravery as well as a lack of a get-away horse.

After the battle, around 5 pm, the horse would have to ride back about 15 to 20 kilometers from Kappel over the Albis to Rüschlikon. Then it faced the difficult task of swimming 1,5 to 2 kilometers across Lake Zurich. It takes good human swimmers around 25 to 30 minutes. Animal welfare organizations would in all likelihood prohibit such a venture today.

The Poem by Conrad Ferdinand Meyer (1825-1898)

|

The commander’s black steed Armour put on Sir Conrad Schmid, to him, they led his brave black steed: “Zwingli, I won’t let that man down and if you join me, I won’t frown.” Men of Küsnacht, hearing these words, thirty in numbers drew their swords. Morn, men and horse aboard at large, loaded with arms, set out the barge. Slowly the day passed, at night news arrived of a lost fight. Horgen tower tolled yonder, soon all bells wailed near and far. And all those who had stayed (home) were standing at the lake, worried. A lucid glow battled in the sky, it did black clouds of rain defy. “Dear God, a nightly wraith!” They saw it rise from the water in awe. Where the silvery moon flowed wrestled and tore a mighty horse. It bristled and closed with speed … “Dear God, the commander’s black steed!” Now the warhorse touched hard ground The pale crowd standing around. Its eyes cast down to earth as if it searched its master there … A boy lifted the animal’s mane “You are bleeding here!” said he The wound had been washed by the lake now it was flowing anew with blood. And every drop heavy and red announces a man’s death. The tower of the command’ry rose white into the moonlit sky. Homewards the black warhorse did move, like in a vault echoed its hoof. Old men, widows, children and maids as in a cortege following its braids. |

Der Rappe des Komtur Herr Konrad Schmid legt’ um die Wehr, Man führt’ ihm seinen Rappen her: «Den Zwingli lass ich nicht im Stich, Und kommt ihr mit, so freut es mich.» Da griffen mit dem Herren wert Von Küsnacht dreissig frisch zum Schwert: Mit Mann und Ross im Morgenrot Stiess ab das kriegbeladne Boot. Träg schlich der Tag; dann durch die Nacht Flog Kunde von verlorner Schlacht. Von drüben rief der Horgnerturm, Bald stöhnten alle Glocken Sturm, Und was geblieben war zu Haus, Das stand am See, lugt’ angstvoll aus. Am Himmel kämpfte lichter Schein Mit schwarzgeballten Wolkenreihn. «Hilf Gott, ein Nachtgespenst!» Sie sahn Es drohend durch die Fluten nahn. Wo breit des Mondes Silber floss, Da rang und rauscht’ ein mächtig Ross, Und wilder schnaubt’s und näher fuhr’s … «Hilf Gott, der Rappe des Komturs!» Nun trat das Schlachtross festen Grund, Die bleiche Menge stand im Rund. Zur Erde starrt’ sein Augenstern, Als sucht’ es dort den toten Herrn … Ein Knabe hub dem edlen Tier Die Mähne lind: «Du blutest hier!» Die Wunde badete die Flut, Jetzt überquillt sie neu von Blut, Und jeder Tropfen schwer und rot Verkündet eines Mannes Tod. Die Komturei mit Turm und Chor Ragt weiss im Mondenglanz empor. Heim schritt der Rapp das Dorf entlang, Sein Huf wie über Grüften klang, Und Alter, Witwe, Kind und Maid Zog schluchzend nach wie Grabgeleit. |

English translation by Jean-Claude Brunner, 2013.

Links

1. Documentation to the 1996 exhibition “Küsnacht in 1525, Ortsmuseum Küsnacht“ (in German)

2. Coat of arms of Konrad Schmid

3. Annual Swimming across Lake Zurich event (in German)

4. Accelerated time video clip of swimming across Lake Zurich (in German)