HOC SIGNO VICTOR ERIS: Constantine the Great and Christianity in Roman Britain

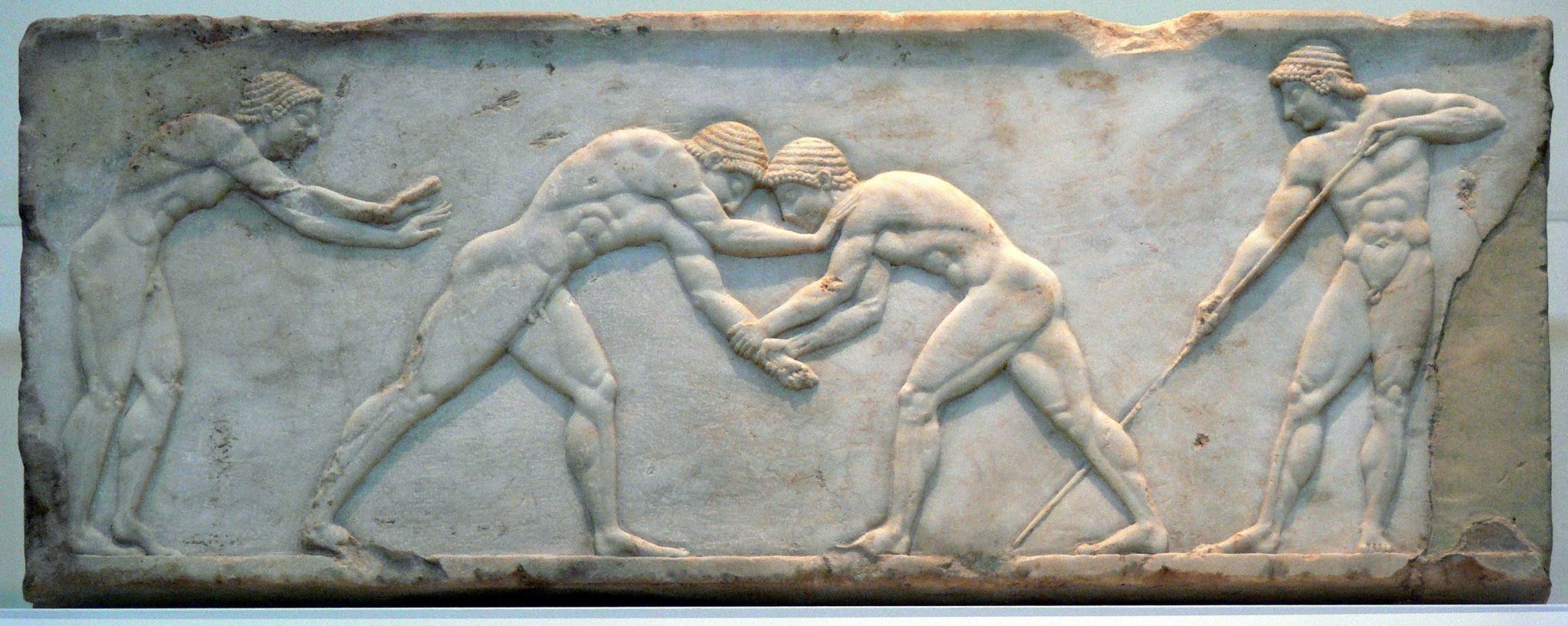

A fourth century Roman Christian ring with chi-rho monogram, bird and tree. Rings such as this were found in Suffolk and Essex and show the gradual acculturation of Christianity into Roman Britain during the reign of Constantine I. 1983,1003.1, AN1406233001© The Trustees of the British Museum. Note that the British Museum photographed the ring with the monogram upside down.

Who was Constantine? Why was he important, and what was his legacy in Roman Britain? At a recent talk on Constantine the Great and the rise of Christianity in Roman Britain, Sam Moorhead, Finds Advisor of the British Museum’s Portable Antiquities Department, looked at the impact of this new religion in the region, discussed the twilight period of pagan Rome, and the rise of early medieval Christianity.

The Pagan Twilight

Constantine the Great (AD 272–337) reigned in the early fourth century. Prior to his rule, the emperor Diocletian (AD 244–312), managed to reform the empire under a new Tetrarchic system where power was distributed amongst four rulers. Unfortunately, according to Moorhead, Britain wasn’t 'playing ball'. In AD 286, there was a rebellion by Carausius († AD 293) who proclaimed himself emperor of northern Gaul and Britain. Carausius was assassinated by Allectus († AD 296), his finance minister, who set himself up as emperor until his eventual defeat by Constantius I (AD 250–306). During these two usurper's reigns, Britain was autonomous for ten years and underwent what Moorhead humorously referred to as, 'Britain’s first Brexit'.

Roman emperors and usurpers were quick to establish themselves with propaganda. Moorhead explained the basics of how propaganda worked in the Roman Empire: one person wrote a treatise, while simultaneously medallions were being churned out in support of that claimant. Moorhead provided an example of an ancient "sound bite" in this quote from Eumenius (b. AD 240) author, and later private secretary to Constantius I, highlighting the ways writers of this period portrayed rulers favourably.

“The overjoyed Britons came with their wives and children to meet you. They gazed upon you as though you had descended from the skies above…For after so many years of the most wretched captivity…they were revived by the true light of our rule.” ~Eumenius

The Great Persecution and the Rise of Constantine

Of the emperors of this era, Galerius (AD 260–311) carried out the most vindictive persecutions of Christians in the early fourth century, specifically between AD 303-311. Galerius staunchly promoted the pagan world and insisted on emperor worship. Christians were viewed as a strange lot because they met in secret, they 'ate' their God (via communion) which was perceived as odd even though Mithraism practiced this as well, and they refused to worship the emperor. For these reasons, they were seen as a threat to the Roman way of life. On the other hand, Constantius I was more tolerant. Moorhead indicated that the West did not have "the same enthusiasm for persecution.”

Galerius’ paranoia of being usurped had him keep Constantine under veritable house arrest. Constantine managed to flee in AD 305, and cleverly evaded capture by having the horses at each staging post killed, thus thwarting Galerius' pursuit. Constantine was able to make it to see his father Constantius I, who was dealing with the Picts (between AD 306-307). Constantius I won the campaign, but didn’t survive much beyond this victory and died in York.

Following the death of Constantius, the next emperor should have been a man in the West called Severus (†307) according to Diocletian’s system, however this was not to be. Constantine spent he next six years trying to deal with his opposition in the empire, leading to a final dramatic showdown with Maxentius (AD 278–312) at Battle of the Milvian Bridge in AD 312, where Maxentius was defeated, and later drowned.

Constantine the Christian Emperor

At this point, it appears that Constantine was already sympathetic to Christianity as he had a bishop in his retinue. Moorhead recounted a story where Constantine saw a symbol in the sky that read HOC SIGNO VICTOR ERIS, “In this sign you will conquer”ensuring victory for him under the banner of Christianity. He heeded that vision and in AD 313, passed the Edit of Toleration at Milan, formalising Christianity as a legal religion in the empire. While the Edict allowed Christians the freedom to practice their religion and not face persecution, it did not grant them special rights.

The following year, he held the first ever Council of Arles where ecumenical matters and the practices of the new Church were discussed. Moorhead said that while Christian organisation in Britain appears to come from out of nowhere, it had been latent, demonstrating that these decisions were already happening in secret. After AD 324, Constantine defeated Licinius (AD 263–325), and became the supreme ruler of Rome. A new capital was built in Constantinople in AD 330: a 'second Rome in the East'. Meanwhile, Britain flourished under Constantine between AD 300-350, and except for Aquitaine and Trier, it was unrivalled in prosperity.

In some ways, Constantine made being a Christian beneficial; a new way to get ahead in the Roman world. Things such as tax benefits were granted to Christians, and money was taken from pagan temples and funnelled into the construction of new churches. He also banned the barbarity of crucifixion. In fact, due to the negative associations with crucifixion, for early Christians, wearing a cross was considered shameful and wasn't considered respectful worship until the Middle Ages.

Christianity After Constantine

When Constantine died in AD 337, he was actually baptised on his deathbed (a common practice at this time: live like a pagan, die as a Christian!) by a contentious Aryan priest named Eusebius (AD 260–340). Moorhead suggested that, naively, Constantine thought that by becoming Christian, everything would sort itself out. He believed the competing Christian sects would respect each other and function together once the stigma of being Christian in the empire had been lifted. This did not happen, and a new battle about the correct way to worship took hold for several centuries after his death. While Constantine certainly paved the way for Christianity to grow, it was not without some backsliding into ancient practices. Julian the Apostate’s (AD 331–363) pagan revival in the 360s shows that it was not all 'smooth sailing' for Christians. Gradually though, Christianity became the dominant religion in the late empire, and continued to be so after its fall in the fifth century. Moorhead showed this progression through various coins, rings, and other artefacts that displayed this mix of pagan and early Christian imagery. For those interested in learning more about this tumultuous transitional period in Britain's history, they can see many of these objects in the British Museum.

Visit: www.britishmuseum.org

Follow: @britishmuseum

Want to learn more about the ancient world? Subscribe to our magazine!