How to Build a Siege Tower… according to Richer of Saint-Rémi

Historians have often lamented that medieval chroniclers offered little detailed information about warfare - these writers were often monks who had no experience in military matters and their reports on battles and sieges were usually at best second-hand accounts (and sometimes they were just literary imaginings). However, you can come across works were the chronicler gives us excellent narratives about these events.

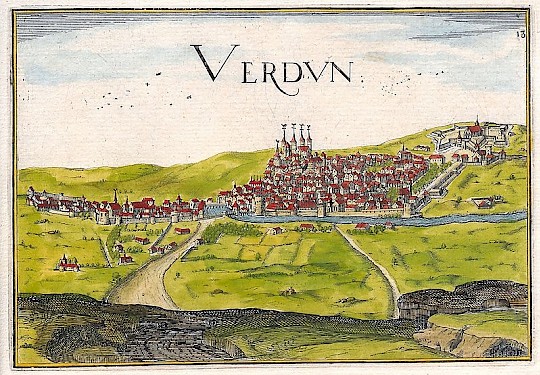

One example of this was the Histories of Richer of Saint-Rémi, which was written at the end of the tenth-century. Richer was a monk living in what is now northern France, and his chronicle covers events from the years 888 to 995. At times he seems to have been very interested in warfare, and was likely an eyewitness to some of the events he describes. This includes the siege of Verdun in the year 985, when Lothar, the king of West Francia, battled a group of rebellious nobles.

According to Richer, King Lothar brought ten thousand men to besiege Verdun, and first made attempt to storm the city. When this failed, his forces surrounded the city and decide to build a siege tower. After explaining that large oak trees were cut down and brought to the the king’s camp, the chronicler gives this detailed description of its construction:

From the trees they cut four beams thirty feet in length, which they placed on the ground so that two of them were positioned lengthwise with a distance of ten feet between them; the two other beams were laid atop them between them; the two other beams were laid atop them horizontally with the same spacing and joined to the beams below. The distance between the joints measured ten feet in both length and width, and the beams extended beyond the joints for ten feet in either direction. At the joints of the beams they used pulleys to erect four forty-foot long wooden piles with an equal distance between them so that they were in the shape of a large rectangle. Then they put rods ten feet in length through each of the four sides at the middle and at the top to bind the piles together firmly. From the ends of the beams on which the piles were resting four more beams were extended upward, reaching diagonally almost as far as the rods on the upper story. The diagonal beams were attached to the vertical piles so that the siege engine would be supported from the exterior and would not wobble. On top of the horizontal rods that connected the engine at the middle and at the top they laid planks and bound them together with latticework so that men could stand and fight atop them and attack their enemies down below with javelins and stones from their elevated positions.

While the siege tower was now built, Lothar and his men still needed to bring it up to the walls of Verdun, which was protected by archers. Richer then relates the next part of their plan:

The gave instructions for four stout logs to be planted firmly in the earth, ten feet deep in the ground with eight feet sticking up. On all four sides the logs were to be reinforced horizontally with solid bars, and ropes would be passed around bars. Both ends of the ropes would lead away from the enemy: the upper ends would be attached to the siege tower, and the lower ends would be attached to a team of oxen. The lower ropes would extend over a much greater distance than the upper ropes, which would be tied around the siege tower so that it would stand between the enemy and the oxen. In this way however far the oxen pulled away from the enemy, the siege tower would be drawn that same distance toward the walls. Through this contrivance the tower, which was put on top of rollers so that it could move more easily, was propelled toward the enemy without any casualties.

Meanwhile, the men inside Verdun were also busy building their own siege tower, although Richer notes theirs was “neither as tall nor as strong.” It was also brought up to the wall to counter the attacker’s siege tower, and the soldiers climbed upon them to continue the battle. Richer writes:

Both sides fought resolutely, and neither gave any ground. When the king drew nearer to the walls, he was wounded in the upper lip by a stone cast from a sling. His men were enraged by his injury and threw themselves into battle with even more ferocity. And because the enemy remained steadfast behind their siege engine and their arms and were not giving any ground, the king instructed his men to employ grappling hooks. These were attached to ropes and hurled at the enemy tower. Once the hooks had caught onto the crossbeams, some men released the ropes, while others picked them up and used them to tilt the tower until it almost fell over. As a result, some of the men on the tower slipped and fell through the joints in the beams, while others leapt off and plunged to the ground; a number of men were also stricken with fear and hid in order to save themselves. The enemy, seeing that they were in imminent danger of death, surrendered to their foes and pleaded for their lives.

King Lothar would not have much time to enjoy his victory - the following year he would be dead, and Richer would go on to tell the story of the rise of the Capetian dynasty that would rule France for the next three centuries. His interest in warfare and siege machines also continued, as he also describes the construction of a battering ram.

The Histories of Richer of Saint-Rémi has been edited and translated by Justin Lake in a two-volume book that is part of the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. You can learn more about the book from Harvard University Press.