More on the Marcomannic Wars

In this article, I will supply further information about the finds that helped to interpret the events in Roman Raetia during the Marcomannic wars, as described in my latest article in Ancient Warfare VII.6. Due to space issues in the magazine, my article had to be shortened, and Josho suggested we pack the missing parts in an online article. Otherwise, the great illustration by Angel Garcia Pinto would have been only a quarter of the size as it is currently, which would have been a pity.

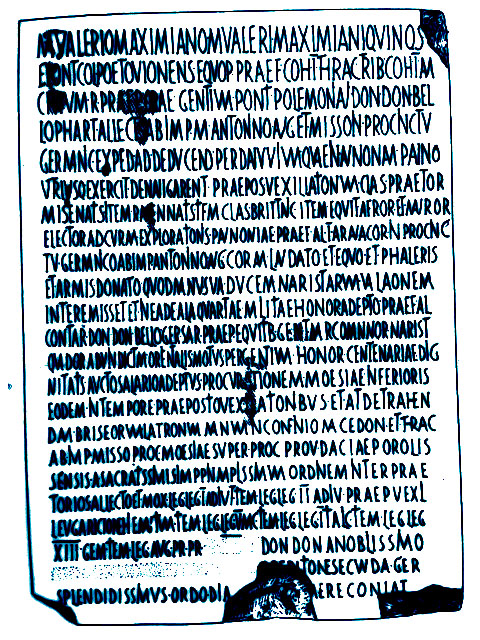

The River Danube played an important role during the Marcomannic Wars, not only as a border, but also as a transport route. The honorary inscription for Marcus Valerius Maximus from Diana Veteranorum is a key in understanding the events I describe on p. 23. Marcus Valerius Maximus had an outstanding career. From a slightly more recent inscription we know that he achieved senatorial rank and even became consul. He later commanded the first ala of Aravacans where he was decorated for killing Valao, the King of the Naristi in battle. Later commands included Legio I Adiutrix, Legio II Adiutrix, Legio V Macedonica, Legio I Italica, Legio XIII Gemina, and – with an imperium pro praetore – Legio III Augusta. The start of this extraordinary career was his excellent organization of the food transports, it seems. A full English translation of the inscription can be found in Brian Campbell’s The Roman Army 31 BC–AD 337: A Sourcebook, no. 114. I have redrawn the inscription from the original publication for you, below:

This image was redrawn by the author after H.G. Pflaum, “Deux carrières équestres de Lambèse et de Zana (Diana Veteranorum)”, Libyca (Archéologie-Épigraphie) 3 (1955), pp. 135–154.

As I have shown on p. 25, the so-called red slip ware was crucial in dating the sites in Raetia that were allegedly destroyed during the wars. Samian Ware or terra sigillata is a type of red ceramic that was mass-produced by the Romans. The centres of production exported their wares all over the Roman Empire. Ceramics have useful archaeological characteristics, as they don’t rot and are very hard (nearly indestructible). As many of the factories have been excavated, we know a lot about the production and the producers likewise.

The ancient potters often marked their wares with stamps, which often featured their names. Sometimes, the fingerprints of the potters are also embedded in the clay, which helps us identity wares. Samian Ware was made in a very special way: after the vessels were finished (which was often a very complicated process in itself, including moulds and stamps or other means of decoration), they were dipped into a very fine mixture of water and clay, called a slip. A slip contains only the smallest particles of the clay used, and a lot of water is needed for its production. When the dried vessels were dipped into the slip, the potters were holding them with their fingers so that, when the vessels were fired, the fingerprints became part of the pottery.

One of the early large pottery centres that can be visited is located in La Graufesenque near Millau in Southern France. It is hard to imagine the size of these pottery-centres, but there one gets an impression. This hard, red type of pottery is omnipresent in Roman excavations, and we know quite exactly when different types, forms, and decorations were in use, and when the potters we know – by name or fingerprint – worked. Because of its durability, Samian Ware is one of the best sources for archaeologists to date sites, layers, or contemporary objects.

The picture above shows one the large pottery-kilns excavated at La Graufesenque.

The picture above depicts specimens of terra siggilata recovered at La Graufesenque.

Before I will tell you more about the equipment seen in the model-painting by Angel Garcia Pinto, I would like to clarify a detail about the Italic legions. During editing a small word got lost. Legio II and Legio III Italica were in fact stationed in Raetia and Noricum until the fifth century AD, and thus operated side by side for about three hundred years (p. 25). If you are interested in the building inscription of the Legionary Fortress at Regensburg, you should check out this page (picture and full text).

Making the illustration

Reconstruction drawings are difficult. They are supposed to create a possible picture of persons of the past with historical attire or equipment in a historical environment. But the paintings are almost always a compromise, as the artist and – if there is one – the author or consultant have to pick out the best available source material.

But complete sets of what someone did wear at a some point in history hardly exist. In some cases, grave inventories can be chosen, but there the question remains whether the person buried actually used or wore the items that ended up in the grave with him. The interpretation of reliefs or paintings is also quite difficult: an artist or craftsman made a depiction of what he saw, and by making it he was influenced by the artistic conventions or styles of his time, as well as by his own skills and mental abilities. So the realism of such sources is always highly questionable, and often leads to misunderstandings, especially when the ancient craftsmen or artists simply copied older art, mixed older art or elements of older depictions with contemporary art or depictions.

Often, ancient art contradicts the archaeological record. For example, we see statues wearing helmets that were out of use for several hundred years at the time when the statue was made. Archaeologists and historians have worked out very minute chronologies for many groups of objects, but for other objects we are left with only a handful of finds for a period of several centuries. A model or painting may hence have to borrow objects from a different time or a different site to fill in the gaps. In other words, some objects may not fit exactly chronologically or geographically.

In museums you can often see this problem solved by plexiglas-cut-outs or the like, replacing or outlining certain objects. In a reconstruction drawing, which is supposed to create something that is complete and is, in itself, also a piece of art, the gaps have to be filled in in such a way that evokes realism. To make a picture like this requires, first of all, a lot of research and a correct attribution of the objects chosen for the painting, and then a lot of patience on the side of the artist.

For this drawing, Angel had to make nine different versions, until everything was to our satisfaction. Details such as the decoration of the infantryman´s belt buckle and the colour sequence of the enamel fillings on it were minutely taken into account. Some of the detail is so minute, it can even hardly be seen in the printed version of Ancient Warfare. For other objects depicted in reconstruction paintings, no finds exist at all, so they are pure guesswork. Here, for example, the crest boxes on the two helmets are educated guesses.

What follows are pictures of objects that were used as a basis for Angel’s beautiful painting. All objects come from the excavations at Regensburg-Kumpfmühl and at Straubing, as mentioned in my article in Ancient Warfare VII.6.

Above, a cavalryman’s greave from Regensburg-Kumpfmühl. It is decorated with two snakes, which were regarded as creatures of good omen and fortune by the Romans. In the centre we see Mars, the god of war. Around these figures are four heads, probably representing the four winds (North, South, East, and West). The elements, taken together, probably conveyed a message like, “Good luck in war, wherever you are.” Made form partially tinned brass.

Eye-protector for a horse from Regensburg-Kumpfmühl. It is decorated with an eagle´s head and wings on the upper right side. The eagle was a symbol of Jupiter, head of the pantheon, and highest Roman State God. Partially tinned brass.

Cheek-piece from a helmet (Theilenhofen-style) found in Regensburg-Kumpfmühl. It shows Minerva, goddess of wisdom and warfare, daughter of Jupiter, and member of the Capitoline Triad.

Spearheads found in Regensburg-Kumpfmühl. Steel.

Picture credits: all the pictures in this article are the property of the author.