Managing a Peasant Army

What happens when thousands of peasants rise up in rebellion and form an army? How do they govern themselves and make sure that order and discipline are maintained? These were issues that came up during the German Peasants War (1524-5), when hundreds of thousands of disaffected peasants revolted in much of central and eastern Germany as well as present-day Austria.

One such group of peasants were known as the Bright Band, and as they formed in the spring of 1525 they created a rudimentary form of democracy. A chronicler reported the field ordinances they established between April 24-27, in which the entire group convened a “ring” to elect its supreme commander.

The regulations adopted by the peasant army reveals the powers and restrictions set on their leadership:

The supreme commander is to be elected by the common bright band, to exercise power over all the people. Each person is to be subject and obedient to him, but with the provisio that the same supreme commander shall not undertake or negotiate anything personally without the will and knowledge of the appointed captains and councillors who have been appointed by the entire band.

Moreover, letters and correspondence sent to the supreme commander had to be shared with the these captains and councillors, and a lieutenant would be appointed alongside him, to handle some of the commander’s duties. The ordinances also offer this helpful rule on where the leadership would be based:

The supreme commander and the lieutenant shall have their lodgings and tents near the cannon, so they can be found by day or night in case of need.

The army, which was divided into troops, also elected several other positions, including captains, color-sergeants, a judge, a provost-marshal (a quasi police-officer), a commander of artillery, a wagon-master, a master of the watch, two quartermasters, a master of the spoils, and a paymaster. The ordinances also added:

Then there shall be appointed a sergeant for each troop, to march alongside the ranks, and whoever shall fall of out of ranks he shall drive back into them. On the march everyone is to remain where he has been ordered and not leave the ranks, on pain of punishment.

The regulations also detail several prohibitions to enforce the Christian morality of the peasant army - for example, no cursing, gambling, toasting, superfluous eating or drinking, and no “unchaste women” were to be allowed into the camp. While on campaign, the band was supposed to protect various peoples:

Item, in this brotherhood and union all women, maidens, widows, and orphans, young children, the old and the invalid, the sick, and women in childbirth shall be protected, defended, left unharmed and free, and shall so remain. Likewise, all millers shall be protected and left unharmed and no plough shall be stolen, but preserved for the common good. No one shall undertake by force or criminal act ot attack or to harm any convent, church, chapter, or like ecclesiastical property without the command and order of the supreme commander and the councillors.

These ordinances offer a fascinating look at how the peasant army operated. You can read the full document in The German Reformation and the Peasants’ War: A Brief History with Documents, by Michael G. Baylor (Bedford/St. Martin's, 2012)

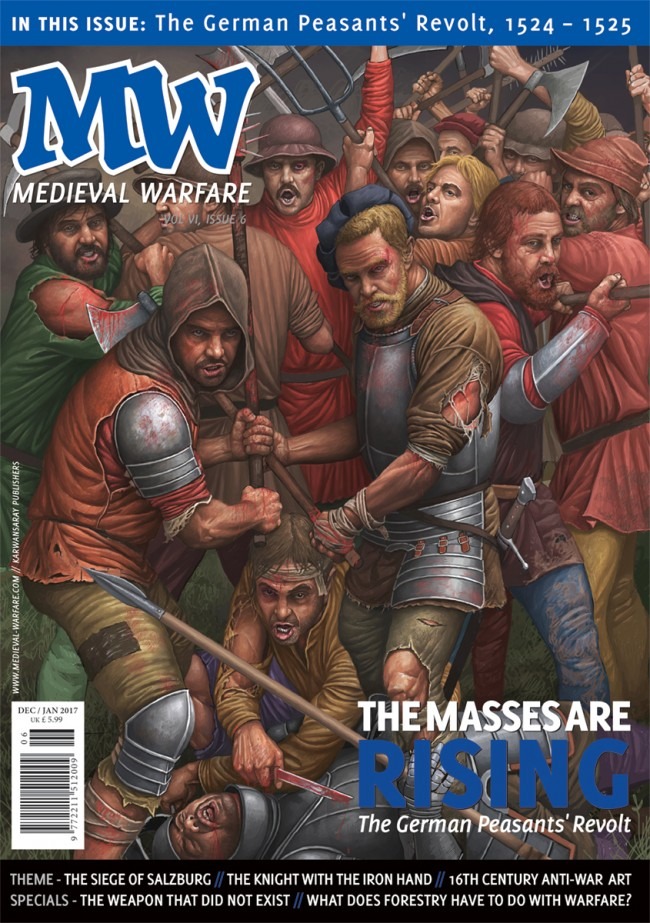

You can read more about the German Peasants War in Medieval Warfare VI:6, which looks at their rise and the chaotic battles that took place as the German nobility moved to crush the revolt. Click here to learn more.