Messages from the Mouse Plague – or, how Herodotus is proved right in the modern world yet again.

Well, this is getting ridiculous! I have been studying ancient Greek and Roman warfare ‘remotely’ (that is from Australia and New Zealand) since the 1990s and I have not been inspired by my Antipodean surroundings for insights into ancient warfare very often. Then this year, 2021, it has happened three times – standing on a beach, at a rural zoo, and the details of the third instance will follow shortly. Now I am worried since, over the years, I may have missed other lessons in the landscape of the Antipodes, which stared at me waiting to be learned (I see the hills and fields of my homeland looking at me disapprovingly, disappointed that I never noticed their lessons). Just as a warning - some of the footage I’ve included for this story is not for the squeamish.

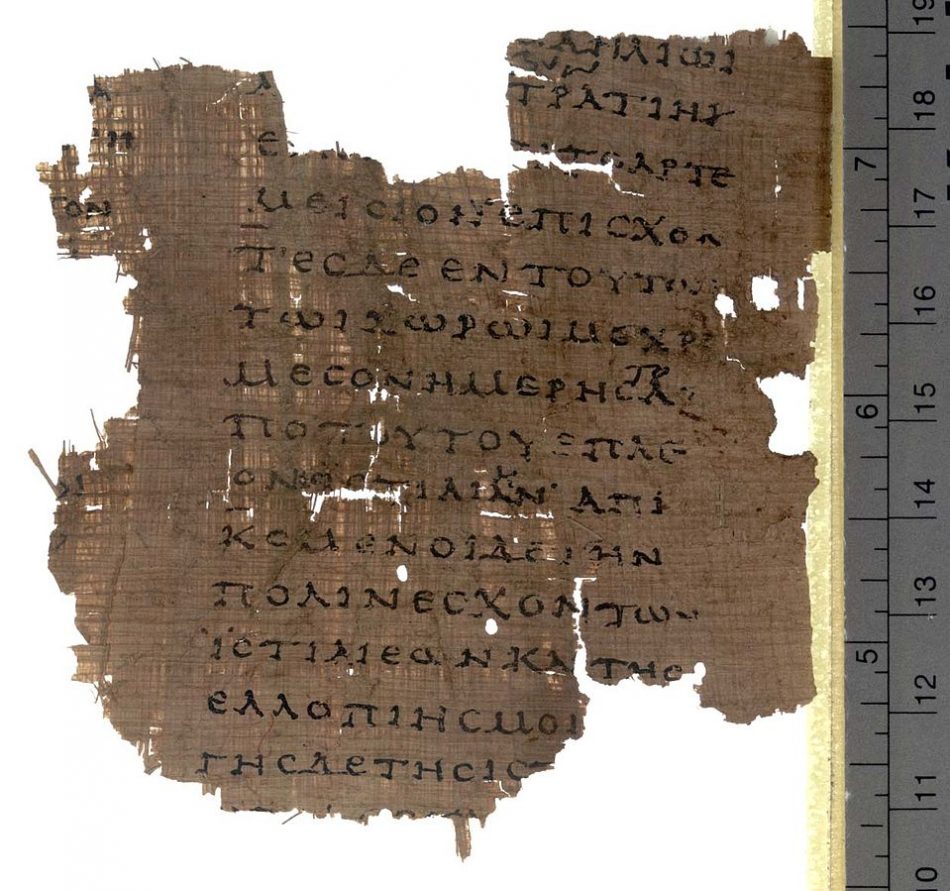

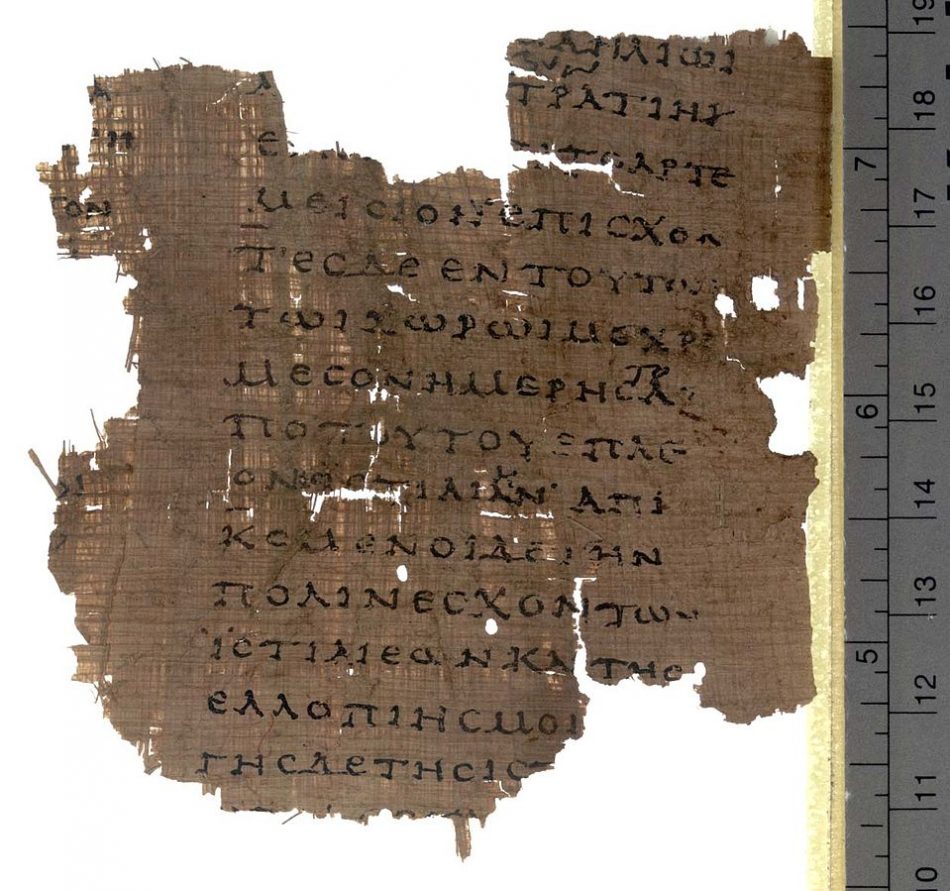

A passage of Herodotus from Book VIII preserved on a fragment of papyrus from Oxyrhynchus

Rural Australia is currently experiencing the worst mouse plague in its history – millions of mice are roaming all over the grain belt of Australia – an area encompassing large parts of New South Wales, southern Queensland, and parts of Victoria and South Australia. The hordes of mice are devouring everything in their path – they have eaten crops, livestock (eating the feet of chickens in their coops, the birds unable to escape). Even machinery and equipment have been on the menu, the mice biting through their wiring has made them burst into flame. If you doubt such stories, similar ones are told of mice sheltering and eating the insulation wires of tanks of the 22nd Panzer Division during winter at the battle of Stalingrad in WWII. In 2021 Australia there are also stories of people being bitten in their beds and being sent to hospital in a critical condition. News channels have posted videos of the numbers of mice and the sheer scale of their numbers and devastation. It would be unimaginable (and unbelievable) were it not captured on film. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X2Q-EPY48wE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9t8tBZegawUMice, mice everywhere

From mid-2020 and into 2021 a combination of conditions gave rise to the explosion in the mouse population. These conditions have been described as a ‘perfect storm’: the end of a drought in the grain belt area of Australia and, following that, a bumper crop combined with optimal weather conditions for mouse breeding. The mild, moist summer of 2020 allowed mice to keep breeding into the autumn, further boosting numbers. Mice began appearing in massive numbers in 2020 just as farmers were harvesting their record crops, the best since 2017. This meant that there was grain in the fields and in storage which provided the mice with ample food. Natural predators were also at a minimum with most having died off during the drought. Extensive burrows and winter crops meant that the mouse population stayed high (and safe) into 2021. Usually, mice are eradicated with poisons, but these take time to be effective and they are expensive – and there is simply not enough poison available to stop the current mouse population. A mouse reaches sexual maturity at the age of only 4-7 weeks, they can have litters all year round and each female is capable of having ten litters of 5-6 young per year – that is a huge, ever-expanding, number of mice. The disaster will continue for some time yet.

The mouse plague

But the remarkable footage of this ongoing mouse disaster is only a part of this story. The other, perhaps unexpected part (at least to anyone who doesn’t know me), is how watching footage of the mouse plague in Australia made me think about the reputation of the Greek historian Herodotus of Halicarnassus (modern Bodrum in Turkey), and how the current disaster in Australia may prove Herodotus’ account of a mouse plague, written in the 5th century BC, and often dismissed as fanciful to actually be right. Several passages of Herodotus have been shown to be accurate in the last few years (after more than two thousand years of doubt) and this mouse plague may provide another example.Herodotus

Often called the ‘Father of History’ (a title first conferred on him several centuries after he wrote by the Roman statesman and man of letters, Marcus Tullius Cicero), Herodotus has also been termed the ‘father of lies’ by less generous readers. This negative attitude has been held from antiquity onwards – the title may have been first given to him by a grammarian named Harpocration, a contemporary of Plutarch writing in the second century AD. Herodotus earned this sobriquet for the sheer number of unbelievable things he included in his Histories; he travelled widely to research the subject(s) of his writings (he was the first writer that we know of to do so), and he also coined the word historiē, meaning inquiry, from which we (obviously) get the word history. Herodotus’ work, the world’s first ‘history’, was written in the middle years of the 5th century BC, probably from the 460s onwards, and was completed by 429. Ostensibly Herodotus’ work was a history of the Graeco-Persian wars fought between the Persian Empire and the city states of Greece from 490-479 BC. His Histories are so much more than that, however, and Herodotus was the undisputed king of the digression. In the nine books of his Histories, Herodotus fills his pages with entertaining stories of every description. He begins his story with myth and brings it down to his own present day (in the 440s BC although the latest events he mentions occurred in 430/29 (the execution of two Spartans at Athens (occurring at 7.137) and which Herodotus states ‘took place long after’ his main story – it is corroborated by Thucydides 2.67). Herodotus’ work was published after 429 and therefore at the beginning of the next ‘great’ conflict of Greek history, the Peloponnesian War, fought between Athens and Sparta and their allies from 431-404 BC. Herodotus was parodied by Aristophanes in the latter’s Acharnians (lines 68-92), a play which was produced in 425, so Herodotus’ work was published before that. Herodotus was probably dead before 413. Herodotus’ all-encompassing narrative contains digressions of every sort: ethnography, geography, etymology, mythology, biology, in fact almost any ‘ology’ you can think of. All are present in (if not invented by) Herodotus. All of these digressions deviate from Herodotus’ core narrative and some might argue that there is more of interest in the digressions than in the main subject of Herodotus’ tale. There is even some pointy criticism of Herodotus by the historian of the Peloponnesian War, Thucydides (the next ‘great’ historian), who makes it clear in his own work (History of the Peloponnesian War 1.1) that he thought of Herodotus more as a story-teller than a historian. Thucydides never names Herodotus, however, but strangely has no qualms naming another (obscure and almost lost to us) author, Hellanicus of Lesbos (1.97.2). Perhaps naming Herodotus would have been a step too far for Thucydides because every historian since Herodotus is his son in some way, whether they embrace the relationship (or the digression) or not. Herodotus was the first writer to have such a wide-ranging subject that looked beyond the history of a particular history or people. And even though his work is chronological, Herodotus took the opportunity to jump backwards (and occasionally forwards) in parts of his narrative to provide additional information not already included. Herodotus was the first to personally investigate his material and explore the meaning, context, and the rationale behind various events and players’ actions. Within the constraints of his knowledge, Herodotus attempts to understand why things happened the way they did. He also tells us (7.152) that he was bound by his mission statement of enquiry at 1.1 – to record precisely what he had been told, but that did not mean that he believed it all. Herodotus states that this overt methodology is a policy that should be considered true of his whole narrative, and this should, in turn, be borne in mind by any who think Herodotus overly gullible in what he records. Any subsequent historian who has explored the meaning, context, or rationale behind events and actions owes their existence to Herodotus. If Herodotus happened to get some of his analyses wrong (and every historian has made mistakes!), whether from flawed logic or the limits of his understanding, these cannot really be held against him. Even in the ancient world, there were other attacks on Herodotus. Ctesias of Cnidus, writing in the early fourth century BC, called Herodotus a ‘myth-monger’ and contradicted Herodotus’ account wherever he could. Plutarch’s On the Malice of Herodotus, written in the 2nd century AD is another example – he calls Herodotus a philobarbaros, a ‘barbarian lover’. More often than not, however, Herodotus’ version of events has been proven correct, even millennia after he wrote – the recent discovery of a boat wreck (known as Ship 17) at the port of Thonis-Heracleion, Abu Qir Bay, on the Nile delta affirmed the construction method Herodotus describes of the baris vessel (2.96). Herodotus’ account was long doubted since no example of such a ship survived. Until, that is, one matching his description precisely was discovered. Thus, Herodotus was proven right almost 2,500 years later!

The hull of a baris built just the way Herodotus describes - (Christoph Gerigk/Franck Goddio/Hilti Foundation)

In another famous example, Herodotus described giant ants (3.102-105) in the furthest north of India which were bigger than foxes but not as large as dogs. When they dug their underground nests, according to Herodotus, they excavated sand that was rich in gold dust. Herodotus also tells us that he was told of this story by the Persians (3.105), so he may not have seen these ‘ants’ himself. The story continues that the Indians harvested the gold-sand and were, on occasion, chased by the ants. The story can easily be seen to reveal the supposed gullibility (or indeed malicious misleading) of Herodotus, and yet, in the 1980s, marmots were discovered in the highlands of the western Himalayas of northern Pakistan on the Dansar plain overlooking the Indus River. When these marmots dug their burrows, they threw up gold-laced dirt which the locals (the Minaro tribe) have collected since time immemorial. Herodotus also described how several of these ‘ants’ were trapped and displayed at the court of the Persian king (it is unlikely Herodotus was given access to the court and we don’t know of him travelling so far east). The Persian name for the marmot is indeed ‘mountain ant’ and so provides a simple explanation for Herodotus’ (actually accurate) story, reporting what he heard from his Persian sources; understanding that he told the truth simply came two-and-a-half thousand years late.

The gold-digging Himalayan Marmot

We have Herodotus’ testament that he travelled as far as Elephantine on the Nile (2.29) and visited the Delta (3.12) and went to the Black Sea (4.76-81). As well as a familiarity with the areas around Athens, the Peloponnese, Delphi, Thebes, as well as several locations in Asia Minor (such as Samos and Miletus), Herodotus also visited Dodona in northwest Greece (2.55), the Thessalian plain (7.129), and Zacynthus (4.195) off the west coast of the Peloponnese. He also travelled to southern Italy, visiting Metapontum (4.15) and other places in the heel of Italy; to the Levant visiting Palestine (2.106) and temples in Phoenicia and Thasos (2.44). He may also have visited as far as Babylon in the east (1.193) and Cyrene in Libya in the west (4.154). Some claim Herodotus did not travel at all, but invented his tales of travels in order to fill his scrolls – that is a provably false accusation. There are some stories that still seem to be false, however. Perhaps the most famous is Herodotus’ account of flying snakes (2.74-75), but, yet again, there may be other explanations for why Herodotus records that story as he does. The digression (parekbasis in Greek and excursus, egressio, excursio, or digressus in Latin) is usually defined as a complete story embedded within another passage of writing. Herodotus has digressions of every length; all of Book Two on Egypt is a digression, and he also includes short passages of a single sentence or two, as well as every length in between. Reading Herodotus, you might even be tempted to argue that his work contains more digressions than it does on-topic writing (something I may share with him). Sometimes Herodotus’ deviation from and return to the ‘main’ story of his narrative is clearly marked, at other times it may be difficult to work out exactly where a digression begins and ends. While some digressions are fleshed out, others are tantalisingly short on details. Sometimes there are even digressions within digressions, such as in his book on Egypt (the construction of the baris is one example). On several occasions, Herodotus promises to return to a subject to give us more detail later in his narrative on a particular topic and Herodotus usually fulfils these promises but on three occasions he does not – a fact which gives insights into Herodotus’ methods – but then virtually everything in Herodotus gives us fascinating insights into something. Those three occasions relate to the fate of Ephialtes following the battle of Thermopylae (7.213), and two to a history of Assyria (mentioned at 1.106.2 and 1.184) which was either never included or was included but has somehow dropped out of the work as it has come down to us. And it is regarding Assyria that the mouse plague in Australia has provided me with insight. This might (once again) reveal that Herodotus may have been right all along in what seems to be an unbelievable tale.Herodotus and the mouse plague

How does this relate to ancient warfare you might ask. Well, the footage of the Australian 2020/21 mouse plague sparked a distant memory of a relatively brief passage in Herodotus’ book two on Egypt. At 2.141, Herodotus includes an account of an Assyrian campaign against Egypt during the reign of a pharaoh he calls Sethos who would have reigned around 700 BC (this passage of Herodotus does not marry with the corresponding passages in Manetho’s Aegyptiaca, written in the third century AD (Manetho has multiple pharaohs in the same period, none with similar names)). No other evidence of Sethos has been found and it has been suggested he was a local priest. How and Wells, commenting on Herodotus’ Histories in the early 20th century considered that this campaign may have taken place in the reign of the 25th dynasty pharaoh, Tarhaqa (one of the Nubian pharaohs, who reigned c. 695-665 BC or perhaps slightly earlier). An Assyrian campaign at this time would marry with the campaigns by the Assyrian king Sennacherib who reigned 705-681 BC, or his son and successor Esarhaddon (or Ashurhaddon) who ruled 681-669. Tarhaqa assisted the alliance against Sennacherib in 701 BC, aiding King Hezekiah of Judah (2 Kings 19:9, Isaiah 37:9). Henry T. Aubin (The Rescue of Jerusalem (2003)) considers that it was this campaign that was the context of Herodotus’ story (but it does not take place in Judah). In 674 Esarhaddon attempted to invade Egypt but was repulsed by Tarhaqa – the defeat may have been one of Assyria’s worst – and it seems that this is the best candidate for Herodotus’ campaign (despite his naming Sennacherib) – perhaps a combination of the two (naming Sennacherib but including details of the campaign under Esarhaddon). A second campaign against Egypt by Esarhaddon in 671 BC was successful and led to the erection of the Victory Stele of Esarhaddon which pronounced the victory of the Assyrians over Tarhaqa and Egypt.

The 25th dynasty Pharoah Tarhaqa

All of which brings us to Herodotus’ tale of a mouse plague. He tells us (2.141): “Next on the throne after Anysis was Sethos, the high priest of Hephaestus. He is said to have neglected the warrior class of the Egyptians and to have treated them with contempt, as if he had been unlikely to need their services. He offended them in various ways, not least by depriving them of the twelve acres of land which each of them had held by privilege under previous kings. As a result, when Egypt was invaded by Sennacherib, the king of Arabia and Assyria, with a great army, not one of them was willing to fight. The situation was grave; not knowing what else to do, the priest king entered the shrine and, before the image of the god, complained bitterly of the peril which threatened him. In the midst of his lamentations he fell asleep, and dreamt that the god stood by him and urged him not to lose heart; for if he marched boldly out to meet the Arabian army, he would come to no harm, as the god himself would send him helpers. By this dream the king’s confidence was restored; and with such men as were willing to follow him – not a single one of the warrior class, but a mixed company of shopkeepers, artisans and market-people – he marched to Pelusium, which guards the approaches to Egypt, and there took up his position. As he lay there facing the enemy, thousands of field-mice swarmed over the Assyrians during the night, and ate their quivers, their bowstrings, and the leather handles of their shields, so that on the following day, having no arms to fight with, they abandoned their position and suffered severe losses during their retreat. There is still a stone statue of Sethos in the temple of Hephaestus; the figure represented with a mouse in its hand, and the inscription: ‘Look upon me and learn reverence.”

The Ne0-Assyrian King Sennacherib

How and Wells call Herodotus’ story of the field-mice childish (in comparison to the “dignified simplicity” of the Jewish story in 2 Kings about the Angel of the Lord) although they did relate the story to the mouse as a sign of plague (though not a mouse plague itself). The losses on the Assyrian retreat may also relate to the mouse plague itself, not only through disease but also, perhaps them eating and spoiling supplies. How and Wells also drew the parallel with Iliad 1.39 (where Apollo, the sender of plague, is invoked as ‘Sminthian’ (from sminthos “mouse”) and 1 Samuel 6:4-5 where a mouse is also used as a symbol of plague. How and Wells also considered that the story in Herodotus related to Sennacherib’s campaign of 701 against Hezekiah and Judah and that a plague overtook the Assyrian army there. In 2 Kings 19:35 we get the biblical explanation: “And it came to pass that night, that the angel of the Lord went out, and smote in the camp of the Assyrians an hundred fourscore and five thousand: and when they arose early in the morning, behold, they were all dead corpses.” The story in Herodotus has parallels and the idea that the mice were the angels of Ptah is attractive in a similar context.

One of the epithets of Apollo (seen here the Apollo Belvedere from the Vatican Museums) was 'Sminthian'

Josephus recorded (Jewish Antiquities 10.14) that Herodotus had included an account of an Assyrian siege of Pelusium – there is no such siege in Herodotus at 2.141 (or anywhere else) but perhaps one originally existed and fell out of the Herodotus text as we have it, or was originally included here or elsewhere (linking back to Herodotus’ unfulfilled promises on the Assyrians). How and Wells also consider that the inclusion of Arabians is an accurate detail since later armies invading Egypt probably also used Arabian guides. The statue of Sethos was probably of Horus (to whom the mouse was sacred), and with whom the Greeks equated Apollo (to whom the mouse was also sacred – seen in ‘Sminthian Apollo’). Strabo (Geography 13.46-48) also discusses mice in connection with Apollo and a story of mice eating all the leather at Hamaxitus in the south-western Troad in north-western Asia Minor. Strabo relates that: “When the Teucrians arrived from Crete (Callinus the elegiac poet was the first to hand down an account of these people, and many have followed him), they had an oracle which bade them to “stay on the spot where the earth-born should attack them”; and, he says, the attack took place round Hamaxitus, for by night a great multitude of field-mice swarmed out of the ground and ate up all the leather in their arms and equipment; and the Teucrians remained there; and it was they who gave its name to Mt. Ida, naming it after the mountain in Crete. Heracleides of Pontus says that the mice which swarmed round the temple were regarded as sacred, and that for this reason the image was designed with its foot upon the mouse.” So, Herodotus’ story of mice eating the leather and equipment of an army is not the only one (and Strabo records that his tale occurred in both the poet Callinus and in Heracleides of Pontus) – but Herodotus’ details are still doubted despite all that. Certain details of Herodotus’ story (such as Sethos himself or the naming of Sennacherib as opposed to the details of a campaign in Egypt under Esarhaddon) seem to be misguided (or reflect his drawing upon a range of foreign materials or summarizing several accounts into one). Most commentators, however, have rejected outright the details of Herodotus’ story – namely that field-mice ate the leather and bowstrings of Assyrian equipment in the night (let alone that they may have bitten and killed the men of the army as in 2 Kings). If you were to ask a resident of rural Australia who has suffered (and continues to suffer) through the current mouse plague whether they thought Herodotus’ story of the devastation that a mouse-plague could reap in a single night was far-fetched, you would receive a very different answer.