Bunk about beards

A (very short) excerpt from a book has been doing the rounds on Facebook and was also posted to the Agade mailing list about why Alexander the Great didn’t have a beard. The excerpt can be found on the website of The Atlantic. It reads that it was ‘adapted’, but I assume it adheres to the original text. Based on the excerpt, though, I wouldn’t recommend you actually buy this book.

It states that the ‘revolution that ended the reign of beards’ (what?) happened when Alexander the Great, in 331 BC, ordered his men to shave their faces before he set off for a showdown with the Persian ‘emperor’. It’s a reference to the Battle of Gaugamela and the ‘emperor’ was, of course, King Darius III. The source for this statement is a brief comment in Plutarch’s Life of Theseus and it’s rightly thought to be apocryphal.

It’s not without precedent, though. In the Life of Theseus, Plutarch’s comment about Alexander telling his men to shave is set within a discussion on wearing your hair short. He makes the claim that the Abantes (an Ionian tribe from Euboea) were the first to cut their hair short so that their enemies couldn’t grasp it in battle. He cites, as proof, a fragment by Archilochus (ca. 650 BC), which doesn’t mention hair at all; make of that what you will. You can read the relevant passage on Bill Thayer’s website.

But obviously, the author can’t leave Alexander’s hairless face unexplained. He writes that ‘Alexander had dared what no self-respecting Greek leader had ever done: shave his face’. Why? The author claims that Alexander wanted to liken ‘himself to the demigod Heracles, rendered in painting and sculpture with the immortal splendor of youthful, beardless nudity.’

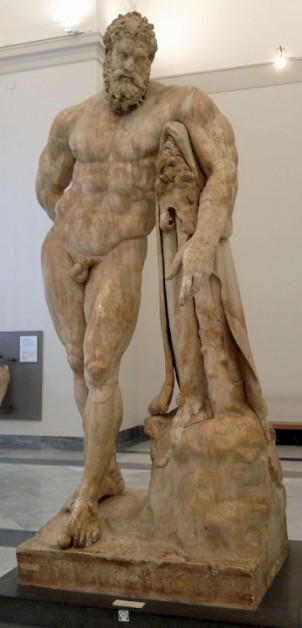

Of course, that statement is wrong. Certainly, there are a few depictions of Heracles that depict him without the beard (nearly all, as far as I can tell, dating from after Alexander), but in the vast majority of cases, Heracles is always depicted as the archetypical ancient Greek man’s man, with a full beard. Perhaps the most famous depiction of Heracles is the Farnese Hercules, currently in the Archaeological Museum of Naples:

It’s a Roman copy (again) of a Greek original dated to the late fourth century BC, or roughly contemporary with Alexander. It may even have been made by Lysippus, Alexander’s personal sculptor (as I wrote in this earlier blog post). The statue was incredibly popular and was copied countless times, including in much smaller, more portable dimensions. You can also check the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (abbreviated as LIMC) and look up Heracles (you can search the French LIMC online, though not all pictures are available). Wiki Commons has loads of vase-paintings of Heracles, for example.

So why did Alexander shave his face? First of all, we can simply compare his hairstyle with that of contemporary men in ancient Greece. In the Classical age, young men typically had short hair and smooth faces, whereas older men had beards (often including moustaches, but not necessarily so), and either short or long hair. (The author is wrong in claiming that ’a smooth chin on a grown man had been taken as a sign of effeminacy or degeneracy’.) Alexander had relatively luscious hair, neither short nor long, but something in between, and a smooth face.

It may very well have been that Alexander the Great simply wanted to appear young – and indeed, we have to remember that he was only 32 years old when he died in Babylon in 323 BC. There may have been more to it than that (perhaps he wanted to be seen primarily as the son of Philip II, especially at first, or he wanted to distinguish himself from other kings), but we simply don’t know for sure. There might not even be a compelling reason to come up with an explanation at all, and there’s no excuse for inventing nonsense.

Updated: rendered unto Plutarch what is rightfully Plutarch’s and added a link to source.