Box office gladiators

Editor’s note: as of issue IX.1, Ancient Warfare has a new segment called ‘Hollywood Romans’. David L. Reinke and Graham Sumner take turns to devote two or three pages to Tinseltown’s treatment of the ancient world. David had the honour to kick things off with an article that compared the success of movies about gladiators with those of charioteers. What follows below is the uncut version of the article published in the issue.

Of charioteers, gladiators, and George Lucas

Noted scholar Adrian Goldsworthy recently remarked that gladiators are one aspect of ancient Rome everyone knows about. “Hollywood has this strange obsession, with virtually every epic or drama set in the Roman period there will be a gladiator or two, hanging about somewhere.”

Indeed, Hollywood has fed us such a steady stream of Roman gladiator movies that it is now impossible to conceive of one without the other. Is it any wonder that the Colosseum, the premiere venue for gladiatorial combat, is the iconic symbol for the city of Rome?

More properly known as the Flavian Amphitheatre, it is truly a marvel of engineering, able to seat over 50,000 spectators and housing a sophisticated system of trap doors and mechanical lifts in the theatre’s floor. Even the ruins themselves are impressive and one can easily understand why the Colosseum was selected to represent Rome.

And yet…

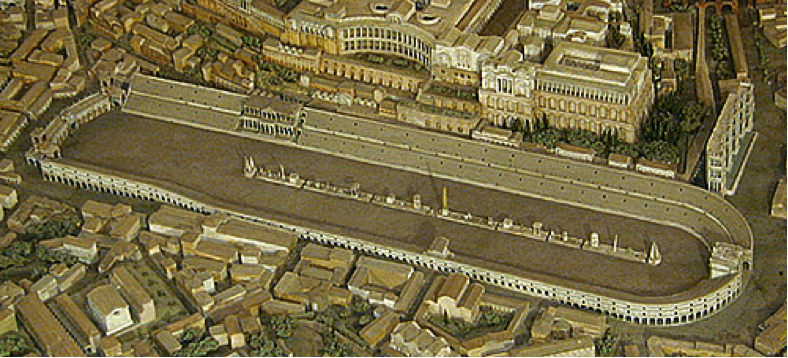

If you were to ask a citizen of ancient Rome what their favorite sports venue was, they would most likely answer the Circus. Rome contained several, the most famous being the Circus Maximus.

Known throughout the empire, the Circus Maximus could seat over 380,000 spectators who watched wild beast hunts, gladiatorial combats, and, most importantly, chariot races. There was perhaps no more popular entertainment in ancient Rome than the chariot races. In fact the fans were so devoted to the various teams (or factiomnes ) that it was not usual for fights to break out, sometimes requiring the intervention of the Guard to restore order, often at considerable loss of life among the civilian populace. (Imagine dispatching the Grenadier Guards in full battle kit to quell the crowds at a soccer game.)

It is interesting to note that modern stadiums, like that in Michigan, seat a mere 110,000 and even the largest in the world, in North Korea, tops out at 150, 000.

So it should come as no surprise that with modern movie audiences too, chariot racing is more popular than gladiator fights.

What?

How can that be true? Wasn’t the film Gladiator a big hit? Didn’t Peter Graves ask Billy if he liked gladiator movies? And what about Spartacus – both the film and the current series on the Starz Network? Besides, Professor Goldsworthy just said that Hollywood is obsessed with gladiators.

Yes, but the numbers tell a different tale.

In his new book, Blockbusting, George Lucas and his editors, Alex Block and Lucy Wilson, have put together a compendium of statistics, facts, figures and some behind the scenes trivia, about 300 of the biggest films in Hollywood history. Although the list is limited to US made films, ranked by their US Box Office receipts, it is none the less an impressive assembly, one in which films about the ancient world are well represented.

The book is divided into decades with each chapter examining different aspects of the film business as well as taking an in-depth look as representative films from that decade. These in-depth examinations include all the vital information about the film (costs, domestic box office, cast and crew, award nominations, etc.) as well as a short essay dealing with the struggle to bring that film to the screen.

Hollywood thinks of the ancient world as two film genres: biblical extravaganzas and sword-and-sandal epics. Of course, not all such films are set in Rome. However, the Roman Empire has been the most often used backdrop for these epics and it is well represented in this book.

A few of the films given the in-depth treatment in Blockbusting :

- Intolerance (1916)

- Cleopatra (1917)

- The Ten Commandments (1923)

- Ben-Hur (1925)

- Cleopatra (1934)

- Samson and Delilah (1949)

- Quo Vadis (1951)

- The Robe (1953)

- The Ten Commandments (1956)

- Ben-Hur (1959)

- Spartacus (1960)

- Cleopatra (1963)

- Gladiator (2000)

- Passion of the Christ (2004)

The associated essays are lively and informative, brimming over with interesting trivia such as:

Kirk Douglas wanted Spartacus to have its premiere in Rome, at the Baths of Caracalla, after the Olympics finished. However, Paramount’s publicity department needed additional time so the film had a more traditional opening in New York on October 6th (page 443).

Quo Vadis, MGM’s extravagant answer to the threat posed by television, was first considered for film back in 1935 with Marlene Dietrich as Poppaea. For the aborted 1942 attempt, both Orson Wells and Charles Laughton were considered for the role of Nero. Even Gregory Peck was briefly cast. When the cameras finally did roll, in 1951, there were 200 speaking parts, 30,000 extras and 120 lions (page 349).

For his 1934 production of Cleopatra, Cecil B. DeMille did extensive research that included ordering a copy of the sixteen-volume French military survey of Egypt. A stickler for authenticity, when he learned that the Romans used snow to cool their wine, DeMille decided to use real frost scraped from the studio’s refrigeration pipes. Likewise, he insisted that real grapes be used on set and had them flown in from Argentina where they were still in season. Even the Asp was real (page 185).

For the 1963 Fox remake, director Joseph L. Mankewicz, having shot over 120 miles of film, wanted to release two three-hour movies: Caesar and Cleopatra and Antony and Cleopatra. However, Fox’s new leader, Darryl Zanuck insisted on a single four-hour epic (page 461).

Given the list above, Cleopatra would seem to be the most popular ancient history topic and even now Hollywood has two more biopics about that fabled queen in development. However, modern audiences, like their ancient counterparts, prefer their entertainment fast and bloody. In the battle for box office laurels, according to Lucas, charioteers not only beat the Queen, but the gladiators as well. (Ben-Hur ranks at #9, while Cleopatra comes in at #34 and Gladiator a distant #202.)

Blockbusting takes a detailed look at the production costs and box office revenues of several films, two of which just happen to be Ben-Hur and Gladiator. In fact, the book directly compares the two, and the numbers are fascinating.

| Ben-Hur | Gladiator | |

| US box office | $704.2 | $223.2 |

| Foreign box office | $608.6 | $321.0 |

| Total box office | $1,312.8 | $544.2 |

| Production costs | $106.7 | $116.8 |

| Print and ads | $98.4 | $59.5 |

| Distribution | $155.7 | $94.6 |

| P&L | $230.0 | -$20.6 |

| Length | 217 minutes | 154 minutes |

| Principal photo | 200 days | 89 days |

| Oscar nominations | 12 | 12 |

| Oscar wins | 11 | 5 |

It would appear from the chart above that Ben-Hur was bigger than Gladiator in everyway, and in fact there was much more riding on the success of the former than the latter.

As the 1950s drew to a close MGM, as a working studio, was in serious trouble. Yes, their library of past films was impressive, but unless they could turn out a new hit the Studio faced bankruptcy. Noticing the success Paramount was enjoying with their remake of The Ten Commandments (still the box office champ of ancient epics), MGM also turned to history, and, staking their future on a single throw of the dice, bankrolled a “go for broke” remake of their own Ben-Hur.

Despite Paramount’s success, MGM was still taking a huge risk given that their original production of Ben-Hur had been fraught with problems and had garnered only modest box office returns. Indeed the new production, besides being expensive, had its own challenges and set backs, not least of which was the death of the film’s producer, Sam Zimblest, who left the set with chest pains and died forty minutes later.

However, the gamble paid off and paid off big. Ben-Hur received 11 Oscars, including Best Picture, and is still ranked in the top ten of All Time US Box Office Champs.

By comparison, Gladiator, though credited with reviving the Sword & Sandal genre in post Star Wars Hollywood and despite receiving five Oscars out of 11 nominations, has yet to turn a profit. Its US Box Office ranking is 202, well below Ben-Hur at #9 or even Spartacus at #158.

It seems that, when it comes to putting down one’s own money, audiences would rather watch the slave turned charioteer than the slave turned gladiator. No doubt it is a matter of personal taste, but in Hollywood taste doesn’t matter, only box office does.

If there are failings with this book they are acts of omission. Blockbusting focuses exclusively on US-made films, and only covers films released prior to 2006. We can hope that future volumes will take a look at films made outside of the US and those made after 2005.

George Lucas’s Blockbusting is a fascinating book and recommended for anyone who views film not as a simple entertainment, but as an art form where money often trumps both artistic merit and critical acclaim.