The massacre of the Usipetes and Tencteri

In 55 BC, the tribes of the Usipetes and Tencteri, which had until then lived on the east bank of the Rhine, invaded northern Gaul. Julius Caesar, who had only recently subdued this area, met the envoys and attacked the tribal warriors during the negotiations, massacring the women and children (story). Dutch archaeologist Nico Roymans of the Amsterdam Free University now claims to have found the battlefield near the village of Kessel-Lith in the Dutch river area.

Although Caesar claims in his Gallic War to have visited Gallica Belgica, until recently there had been no sites in the Low Countries that could be connected to Caesar’s presence or a Roman massacre. Over the past years, however, Roymans has tried to shed light on the arrival of the Romans and the violence they used. Roymans: “Think of indirect evidence especially, such as treasures buried to hide them from looters, information about depopulation, or ritual burials of weapons.”

And of course there’s Caesar’s own story, his books about the Gallic War. “In the fourth book,” Roymans says, “Caesar writes without any embarrassment how he massacred the Usipetes and Tencteri.” The Roman commander relates how the powerful Germanic tribe of the Suebians had forced the two tribes to leave their homeland, how they then crossed the Rhine, and asked Caesar for permission to settle on the west bank of the river. He refused the request and ordered his men to attack the camp. Men, women, and children tried to escape, but they could not pass “the confluence of Meuse and Rhine”, where they had been killed, or had thrown themselves into the rivers.

So far, no archaeological traces have been found of the camps of either the Germanic migrants nor of the Roman soldiers. But there is a lot of evidence for the massacre. “In a very ancient interpolation in the text, which can be found in several Medieval manuscripts of the Gallic War, we read that the confluence of Meuse and Rhine was eighty Roman miles (120 kilometers) from the sea. That branch of the Rhine is now called Waal, which nowadays comes close to the Meuse at Kessel-Lith. It’s about ninety kilometers from the North Sea, but if you take the meanders into account, it fits.”

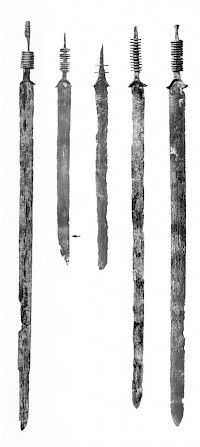

Roymans was aware of archaeological finds from this area. They had been dredged from the water in the last quarter of the twentieth century and had been collected by amateurs. “Large quantities of iron swords, spearheads, fibulae, belt hooks, and bones. Almost all of it is from the first century BC.”

“Belt hooks are typical for the dress of Germanic women and offer a first clue for the identification of the people who wore them. Anthropological research shows that the bones belong to men, women, and children; at least a hundred individuals have been identified. Radiocarbon dates prove that three-quarters belong to the first century BC. On many of those bones, the traumata of violence are still visible, like the woman whose eye-socket had been pierced by a spear.”

Roymans was not convinced yet, so he asked bioarchaeologist Lisette Kootker (VU University Amsterdam) to investigate the strontium isotopes of the enamel in the teeth of three individuals. Kootker: “This helps us identify the area where someone was born. These three people were certainly not from the Dutch river area. As a control, we also checked a bone that has been dated to the seventh century BC, and which is known to be from someone who was born in this area.”

Why did Caesar kill those people? Why did he speak so openly about it? Roymans: “He depicted the two tribes as very large and presented them as a real threat, so that he could present himself as protector of Rome. In reality, he must have been driven by lust for power and means to enrich himself.”

Perhaps it is for that reason that he claimed to have killed everybody, a claim that is certainly not true, because the Usipetes and Tencteri are still mentioned in the first century AD. However, if he claimed to have exterminated them all, he could keep the captives out of his official books, sell them as slaves, and pocket the profits.

When asked for his opinion, historian Jona Lendering, author of Edge of Empire and editor of Ancient History Magazine, is at first skeptical. “In those days, there were more fights between Germanic tribes and Romans, or between the tribes themselves. Still, the location of Roymans’ finds, so close to the confluence of Meuse and Waal, is really suggestive and I am tempted to believe he is right.”