A 13th-century Crowdfunding Campaign for a Templar Castle?

One of the best written descriptions we have about a medieval castle is De Constructione Castri Saphet, a short pamphlet that describes the Templar castle of Saphet. Was this work written to help raise donations for the military order, a 13th century version of crowdfunding?

Saphet Castle is located near the Golan Heights in present-day Israel, but during the 12th century it was part of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. A fortress was built there during the middle part of that century, and by 1168 was handed over to the Knights Templar to serve as one of their bases. However, twenty-years later it was captured by the Ayyubids under Saladin, and was not returned to Templars until the year 1240.

De Constructione Castri Saphet is an account of how Saphet was rebuilt. The work gives credit for its reconstruction to Benoit d’Alignan, Bishop of Marseilles, who visited the Holy Land on a couple of occasions. During his trip in 1240, he undertook a pilgrimage to Damascus, and on his return he came upon Saphet, which is then described as “a heap of stones without any building where once there had been a noble and famous castle.”

The anonymous author of De Constructione Castri Saphet then writes:

When the bishop had inquired carefully about the surroundings and district of the castle, and why the Saracens were so fearful of it being built, he found that if the castle were constructed, it would be a defence and security and like a shield for the Christians as far as Acre against the Saracens. It would be a strong and formidable base for attack and provide facilities and opportunities of making sallies and raids into the land of the Saracens as far as Damascus. Because of the building of this castle, the Sultan would lose large sums of money, massive subsidies and services of the men and property of those who would otherwise be the castle and would also lose in his own lands casals [villages] and agriculture and pasture and other renders since they would not dare to farm the land for the fear of the castle. As a result of this, his land would turn to desert and waste and he would also be obliged to incur great expenditure and employ many paid soldiers for the defence of Damascus and the surrounding lands. In brief, he found from common report that there was no fortress in that land from which the Saracens would be so much harmed and the Christians so much helped and Christianity spread.

Bishop Benoit then travelled around the Kingdom to gain support for the rebuilding of the Saphet, meeting with the Grand Master of the Templars to convince him that it could be done. He was successful in getting approval from the Grand Master and other officials, and soon “an impressive body of knights, serjeants, crossbowmen and other armed men were chosen with many pack animals to carry arms, supplies and other necessary materials. Granaries, cellars, treasuries and other offices were generously and happily opened to make payments. A great number of workmen and slaves were sent there with tools and materials they needed.”

Hugh Kennedy notes in his book Crusader Castles that it took about three years for Saphet to be rebuilt. He adds that “according to late medieval travellers, the fortress was one of the most magnificent constructed by the Crusaders and was certainly one of greater glories of the Templars.”

This praise includes the second part of De Constructione Castri Saphet, which describes how the Bishop returned to the Holy Land in 1260 and visited the fortress. The account gives many details about the castle and the territory around it, including the sizes of various buildings, and how it much cost to guard it:

For we asked and carefully inquired from the senior men and through the senior men of the house of the Temple, in the first two and a half years, the house of the Temple spent on the building the castle of Saphet, in addition to the revenues and income of the castle itself, eleven hundred thousand Saracen bezants, and in each following year more or less forty thousand bezants. Every day victuals are dispensed to 1,700 or more and in time of war, 2,000. For the daily establishment of the castle, 50 knights, 20 serjeants brothers, and 50 Turcopoles are required with their horses and arms, and 300 crossbowmen, for the works and other offices 820 and 400 slaves. There are used there every year on average more than 12,000 mule-loads of barley and corn apart from the victuals, in addition to payments to the paid soldiers and hired persons, and in addition to the horses and tack and arms and other necessities which are not easy to account.

The pamphlet practically raves over the location, including a description of the fertile land around Saphet:

…has a temperate and healthy climate, rich in gardens, vines, trees and grass, gentle and smiling, rich and abundant in the fertility and variety of fruit. There figs, pomegranates, almonds and olives grow and flourish. God blesses it with rain from the sky and richness from the soil and abundance of corn, vines, oil, pulses, herbs and choice fruits, plenty of milk and honey…

The author even adds in a few words on its defensive capabilities:

Among the other excellent features which the castle of Saphet has, it is notable that it can be defended by a few and that many can gather under the protection of its walls and it cannot be besieged except by a very great multitude; but such a multitude would not have supplies for long since it would find neither water nor food, nor can a very great multitude be near at the same time and, if they are scattered in remote places, they cannot help one another.

Why was this work written? Hugh Kennedy explains that the author “may have composed it simply to commemorate the bishop’s work but it seems more likely that this is a fundraising treatise, designed to be read or used as a basis for sermons and appeals. The emphasis on the cost of the castle, its continuous usefulness to the Christians and, in the final section, its role in protecting well-known Holy Places, suggest that this is a strong possibility.”

However, the opportunity for people to support Saphet would soon close. In 1266 the castle was besieged by the Mamluks under the Sultan Baybars, and the Templars were tricked into surrendering it. The Mamluks then strengthened and expanded Saphet, and the castle stood until the 19th century when it was demolished by an earthquake.

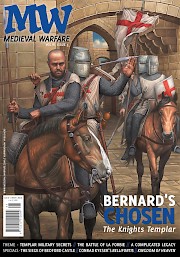

You can read the English translation of De Constructione Castri Saphet as an appendix to Crusader Castles by Hugh Kennedy. You can learn more about the Templars in the latest issue of Medieval Warfare.

You can read the English translation of De Constructione Castri Saphet as an appendix to Crusader Castles by Hugh Kennedy. You can learn more about the Templars in the latest issue of Medieval Warfare.