Too tired to fight? Harold Godwinson’s Saxon army on the march in 1066

The Battle of Hastings was arguably the most important action ever fought on British soil. There, on 14 October 1066, William “the Bastard”, Duke of Normandy, won a kingdom and changed the face of Britain forever.

Many historians postulate that the Saxon army which encountered the Normans at Hastings was already greatly depleted by a forced march from the earlier Battle of Stamford Bridge in Yorkshire on 25 September 1066. Certainly King Harold’s Saxon army was having a busy autumn. Near the end of September they had marched the 200 miles (320 km) from London to Yorkshire to repel the invading forces of the Viking ruler Harald Hardrada and his ally, the English king’s brother-turned traitor-Tostig. Then, at the end of the month, the Saxon King received the unpleasant tidings that Duke William had landed on the south coast of Britain. Turning his army about, Harold had no alternative but to march all the way back south in order to meet the new, but not unexpected, Norman threat. By contemporary Western standards this sounds like a tall order, and it is frequently argued that only the elite mounted Saxon housecarls would have been able to make the journey in time.

The question remains as to whether the arduous trek from Yorkshire materially reduced the numerical strength and combat effectiveness of Harold’s army as it raced 270 miles (432 km) for the Sussex coast to confront the Norman invaders. It did not. Why? Because the Saxon army which fought the Normans at Hastings was not the same bloodied Saxon host which triumphed at Stamford Bridge.

King Harold’s army marches north

The lighting campaign Harold conducted in the north of England against the Norsemen of Harald Hardrada and Tostig was masterful in that it involved speed, surprise and overcoming very difficult terrain. Northern Britain in the mid-eleventh century was divided culturally and politically from the rest of the nation, and was generally left to its own devices. Hard to reach – only a few roads traversed the Humber Estuary and the bogs and swamps of Yorkshire and Cheshire connecting the north and south – the north was an isolated and barren region. The 200 mile (320 km) journey from London to York usually took two weeks, or more depending if the roads were passable.

The fastest way to travel from the south to the north of England was by ship along the country’s east coast. Unfortunately for Harold, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, a few days before he heard of the Viking incursion in the north, he had disbanded his army which he had assembled some months before in anticipation of an appearance by the hostile William Duke of Normandy. The army had to be broken up, since the customary 60 day enlistment period for most of his soldiers had come to an end. It was also becoming more and more difficult to keep the army and navy intact due to the problem of supplying them. On 8 September, Harold got wind of Hardrada’s northern incursion. Prior to that alarming news the Saxon fleet had been sent to London, but, as reported by theAnglo-Saxon Chronicle, it had lost many vessels as it made its way to the city around the south coast. The damage to his fleet may have been the prime reason the king did not sail for the north instead of making the arduous overland journey on foot. Given favorable wind and tides a sea voyage would have taken about three days. Thus, Harold could have avoided much of the stress and strain on the troops making the move north, as well as the burdensome supply requirements (i.e. passable roads, wheeled transport and draught animals) needed to support such a march to the north.

Regardless, the Saxons, after leaving London in the middle of September, arrived in Yorkshire, near Tadcaster, on 24 September. They had covered 200 grueling miles in a little over a week, making an impressive 22 to 25 miles (35-40 km) a day. The army’s rapid progress surprised the unsuspecting Norsemen, resulting in their complete defeat at the savage Battle of Stamford Bridge on 25 September.

Having successfully disposed of one menace to his throne, sometime between 29 September and 1 October Harold was notified that the long awaited invasion of Saxon England by William of Normandy had taken place. He now had no choice but to return to the south to deal with this new threat.

Harold marches south

From York the King raced southwards toward London. Again, the earlier damage to his fleet prevented him from moving south by water. But Harold did not lead the same army he had taken north in September. Most likely, he only led the core of that force. These would have included his housecarls (originally mercenary troops recruited from Scandinavia, this elite professional military force rode to battle but fought on foot; read more about them in Raffaele D’Amato’s article in Medieval Warfare II-1), as well as his brother Gyrth’s contingent of similar troop types. Absent on the return to the south were many of Harold’s original army. This was due to the heavy casualties the army had sustained at Stamford Bridge, as well as a lack of vital supplies and transport needed to move all soldiers. This was largely the result of the king’s inability to procure these resources from the North Country. (Remember, the crown had no great landed estates or financial institutions in the north from which it could recruit soldiers or gather needed supplies for its army, not even if he paid for it. Politically, as well as culturally, the authority of the crown was almost nil in this part of England.)

The northern earls and their men were also absent from the march to the south. They had suffered severe losses at the Battle of Fulford (25 September 1066), where Hardrada’s army crushed the local Saxon forces in Yorkshire under the Northern Earls Edwin and Morcar (for more information, readCharles Jones’ article about the Battle of Fulford in Medieval Warfare I-3). It took these regional leaders time to raise and equip new forces and then march south, which explains why they were not present at Hastings to aid their king.

An old army replaced by a new one

By 8 or 9 October, Harold reached his capital. Before his arrival in London, he had sent out royal summons to the different shires in the Midlands and southeast of England, calling on his subjects to muster for military service. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle D version refers to this as the raising of a new army. The classes of recruits for this new host took two forms: the ‘general’ fyrd, and the ‘select’ fyrd. The former were made up of all the freemen of an area which were obligated to turnout for the defense of their locality only. They had practically no military training. The latter was a body of part time militia that would serve the king outside of the region they were originally raised from (more information on the fyrd, as well as on King Alfred the Great’s military reforms, can be found in Medieval Warfare III-5). By these calls to the colors, Harold was able to raise another army – a new one – and have it assemble at London. Further, this meant that the bulk of this new army would be reasonably rested and supplied and ready to follow the king to the Sussex coast where the Norman invaders had landed. On the minus side of the ledger, except for the king’s household fighters – the housecarls – the bulk of the army Harold lead to Hastings against the Normans would have been untested in battle.

After arriving in London, Harold lingered there for a day or two, resting his veterans from the campaign in the north and absorbing daily arriving reinforcements. Then the king moved the 60 miles (96 km) to where the enemy was encamped, near Hastings. This Saxon maneuver was conducted at a more leisurely pace than the march to York the month before. The three day sojourn, at a rate of about 20 miles a day, did not over overtax the troops, assured secure sources of supply, kept the army concentrated, and allowed for reinforcements to join the main column in a timely manner.

Before the king departed for the coast, his mother and brother, according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle D version, begged him to be cautious, saying to him that, “You have just returned worn out after the war against the Norwegians; are you now hastening to move against the Normans.” Some historians point to this as a sign that the army Harold was gathering was itself tired and in disarray due to its exertions on the march and in battle since September. But the above facts suggest that it was not the army that the king’s relatives were concerned about, but Harold’s current health and judgment. The force he was leading against the Normans was fresh, strong and probably possessed cohesion; the worry in the royal court was about the mental and physical fatigue Harold must have been suffering from as a result of his exertions of the last few weeks.

A tired Saxon army, or an understrength one?

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle E version suggests that Harold set out from London too soon (on 11 October), “before all his host came up.” John of Worchester expanded on this idea by writing that the king had only ”half his host” when he marched for Sussex. But the author then goes on to relate that the narrowness of the Saxon position at Hastings prevented a full deployment of Harold’s army, rather than there being a depleted number of English troops. This seems logical, since the length of the coming fight – which commenced at around 9 am and ended at dusk (about 8 pm) – and its intensity makes it likely that there was no lack of English troops involved in the engagement.

Norman sources, such as William of Poitiers, chaplain to Duke William, suggest that Harold’s motive for quickly coming to grips with the Normans was to prevent further damage to the king’s estates in Sussex, which the invaders had been ravanging since early October. But he never says that the king’s haste made him move with only a part of his army, or that the Saxons were understrength when they came to Hastings.

Other Norman accounts mention the possibility that Harold’s movements were prompted by the desire to repeat the surprise attack on Hardrada, but this time with the Duke of Normandy as the target. This is a logical conclusion, since Harold was a bold commander who had been successful with such stratagem very recently, i.e. at Stamford Bridge. This would seem to counter the argument that the Saxon army was tired or below strength. A force in such a condition is usually unable to execute such ambitious schemes with precision and celerity. Further, this ties in nicely with the general attitude toward war of Anglo-Saxon military forces of the period: the desire to come to grips with the enemy as soon as possible and engage in a decisive battle. (In contrast, the Norman practice stressed campaigns of maneuver and a proclivity towards siege warfare to bring about successful military conclusions).

The physical condition of Harold’s army is further brought in to relief on the eve of the Battle of Hastings by the remarks of William of Jumieges in his The Gesta Normanorum Ducum (‘Deeds of the Dukes of Normandy’), and the twelfth century Medieval historian William of Malmesbury in his Gesta Regum Anglorum (‘History of the Kings of England’). The former states that the English army had marched all night, arriving on the battlefield at dawn. Common sense would indicate that the men would have been worn out by this recent exertion. But William of Malmesbury says that the Saxons spent the entire night before the battle singing and drinking. So were the Saxon’s on the move during the time immediately before the fight, or were they encamped resting and enjoying themselves before the blood bath of the next day? Either way, the Saxons fought very well and continuously at Hastings which indicates neither fatigue nor the poor morale which accompanies tired soldiers. On the contrary, both stories seems to point to a force brimming with confidence.

Even after the Saxon defeat at Hastings, there was no sign of a tired or disheartened English army. William of Poitiers wrote that after the battle, London was crammed with Saxon troops, “A crowd of warriors from elsewhere had flocked there, and the city, despite its great size could scarcely accommodate them all.” A portion of these men were doubtless soldiers previously summonsed by Harold, others were survivors from the battle, or as the 800 line poem Carmen de Hastings Proelio (‘Song of the Battle of Hastings’) recorded “the obstinate men who had been defeated in battle.”

Conclusion

The Battle of Hastings pitted opposing armies of approximately the same strength (i.e. around 8,000 men) against one another. The ensuing engagement lasted about 11 hours with heavy fighting and severe losses taking place the entire time. The endurance of the Saxon command, assailed by Norman heavy cavalry, showered by enemy arrow volleys, as well as the launching of two major attacks of their own, shows that that force was in no way a spent or tired one before the battle. In fact, it seems to have been a newly raised and rested army which took the field a few weeks before Hastings and in no way was depleted in manpower or resolve, though it is possible that the lack of experience of the newly raised troops gave the Normans another edge in battle.

Further reading

- G.N. Garmonsway (ed.), The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles. Oxford 1972.

- R.R. Darlington and P. McGurk (eds.), John of Worcester, 3 vols. Oxford 1995.

- William of Poitiers, Gesta Willeimi ducis Normannorum et Regis Anglorum.

- William Malmesbury, Gesta Regum Anglorum.

- Guy Bishop of Amiens, The Carmen de Hastings Proelio.

- I.W. Walker, Harold: The Last Anglo-Saxon King. Gloucester 1997.

- P. Rex, A New History of the Norman Conquest. Chalford 2009.

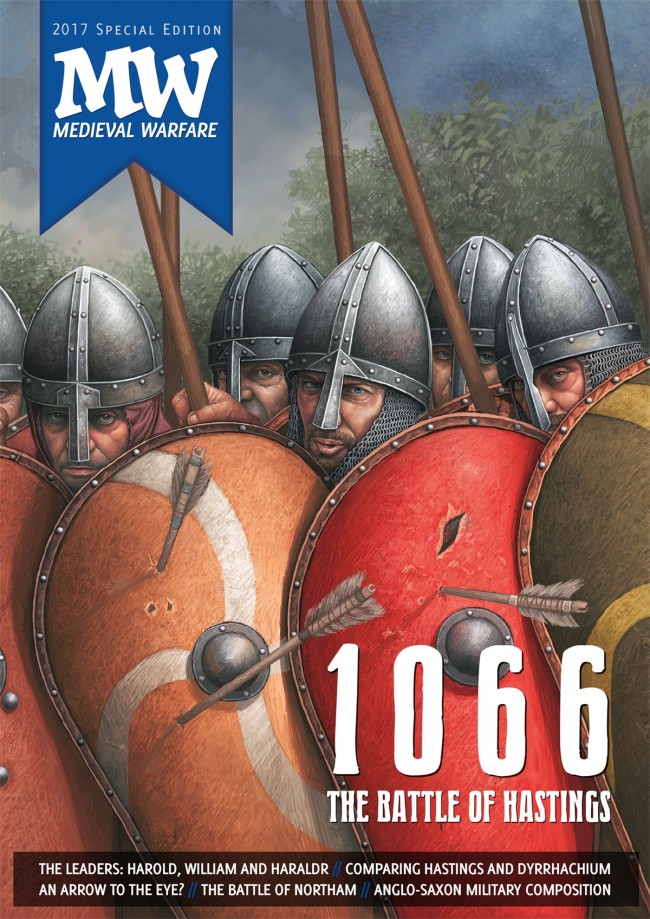

Check out the special issue of Medieval Warfare magazine on 1066: The Battle of Hastings

1 comment

Cant be asked to read it all ngl tried to cheat on a test with it…