Book Review: The Dignity of Roman Labour

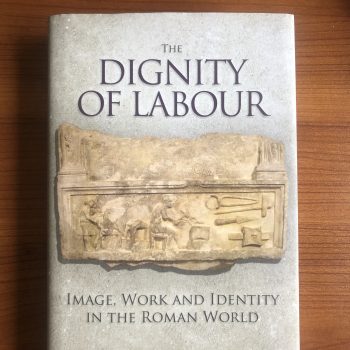

The Dignity of Roman Labour: Image, Work and Identity in the Roman World

The Dignity of Roman Labour: Image, Work and Identity in the Roman World

By Iain Ferris

ISBN-13: 978-1445684215

Publisher: Amberley Publishing (2021)

Price: £20

Reviewed by Sandra Alvarez

Soon to be released for the New Year in January 2021, Iain Ferris has teamed up again with Amberley Publishing to bring about a book on the representation of labour in art in the Roman world. Although relatively short (at 288 pages) the book provides an in-depth look at how art reflects Roman workers to their society through frescoes, mosaics, pottery, and especially funerary stelae. Ferris is careful to keep to the topic and informs the reader early on that he will not be discussing the work itself so much as what the images of such labour aimed to portray to fellow Romans about one's identity, status, and value to society from the top down. The book also primarily discusses labour that is taken on voluntarily, thus Ferris states clearly that he will not be including slaves, gladiators, and prostitutes since these were positions of "coercive participation" (p.8) where their identities were "thrust upon them in many cases rather than chosen" (p.9).

The chapters are broken down by occupational groups. Chapter 1 deals with 'those who built the city', architects, manual workers, masons, blacksmiths and mosaicists. It also touches on the respective deities that were rendered in the art that these labourers felt a kinship with, such as Minerva for weaving and craftsmanship, and Prometheus for those who worked with fire because he gave mankind fire. Chapter 2 deals with the images of 'those who fed the city', i.e., bakers, millers, and butchers. In this chapter, Ferris discusses at length the meaning behind the famous and rather ostentatious tomb of Eurysaces the Baker. Chapter 3 moves onto 'those who clothe the city' and the cultural importance of the textiles trade and its various representations in art, including leather workers, fullers, and shoemakers. Clothing was especially important in Roman society and it signalled one's social status and identity. While certain lines of work were shunned by elites due to their association due to their distasteful processes (such as tanning), or because they were associated with manual labour, some workers, such as fullers – who were basically launderers who washed clothes with urine and other chemicals – were not completely shunned in places such as Pompeii where wealthy patronage allowed them to build a guild headquarters.

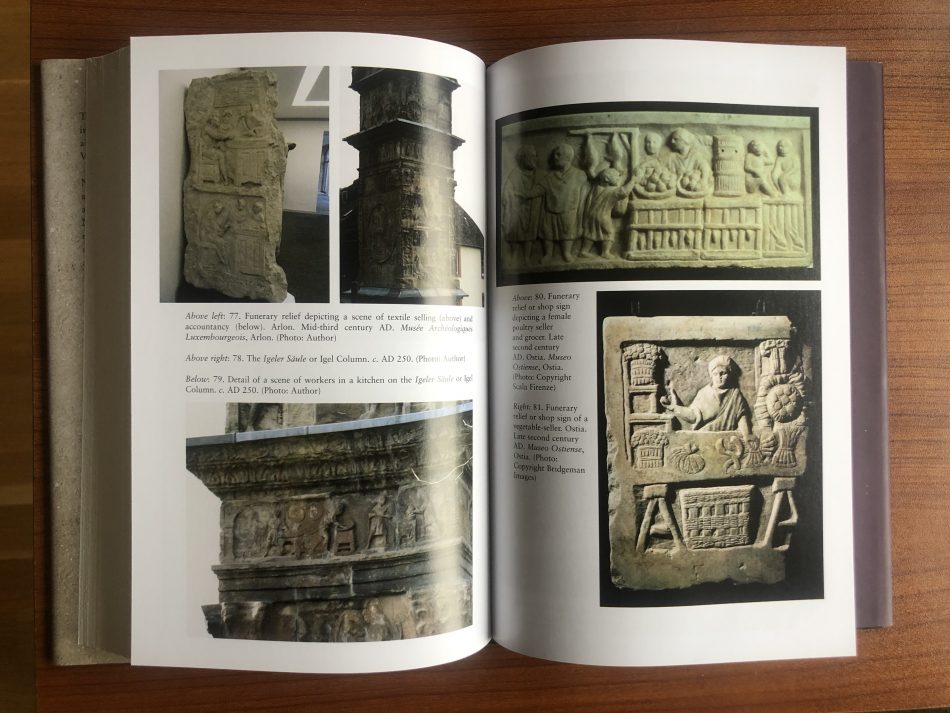

The Dignity of Roman Labour contains 32 pages of beautiful coloured plates depicting scenes of most of the occupations discussed within the text. ©Sandra Alvarez

Chapter 4 deals with metalworkers and discusses the importance of the trade that equipped Rome’s armies and was one of the most highly respected and admired crafts. Ferris briefly talks about the delicate subject of the use of child workers in mining - and the rare depictions and inscriptions of this line of work in funerary stelae. Goldsmiths, jewellers, bronzesmiths and coppersmiths, and those who did the important and strenuous job of working in the Roman mint are also covered in this chapter.

Chapter 5 takes an interesting turn in that it moves to the discussion of maker’s marks with a focus on pottery and glass. It details the significance of a name in Roman society as something that could immediately tell the viewer whether one was a Roman citizen or a slave, or represent one’s workshop or individual work. While maker's marks are often associated with quality craftsmanship today, Ferris points out that this was certainly not the case in ancient Rome. Maker's marks could also indicate the level of output by a potter or other craftsmen - and could be used as a way to control and count production across the empire. Chapter 6, "Empire on the Move" deals with shipbuilders, wagon makers, and wine merchants - those who travelled or helped build transportation for trade. Wrapping up the text, the last few chapters are dedicated to the subject of allegory in labour art, working communities, such as occupational associations, women's work, gender bias in representation, and lastly, the surge of freedmen and women who proudly displayed their professional identities through the artwork and inscriptions that adorned their funerary monuments.

While the book provides a cursory overview of workshops, working conditions, societal perceptions, and the types of tools used for each trade, it is an excellent resource for understanding how individual workers forged their identities and asserted agency through their representations in art. This book is the perfect addition to the shelf of any art historian, Roman historian, or social historian look to better understand the important connections between labour and art in the ancient Roman world.

Love ancient history?

Want to learn more about the Romans?