The Swedish History Museum

When the International Ancient Warfare Conference in Gothenburg was over, I travelled onwards to Stockholm and spent a few wonderful days there. Stockholm is a beautiful city with lots of really good museums. One of the most interesting, from the point of view of an archaeologist, is the Swedish History Museum.

One of the complaints that I’ve vented in the past about archaeological museums is that so few of them actually explain what archaeologists do, including details on how the past is continuously made and remade by those who study it. The Swedish History Museum actually tackles those questions head on and does a lot of other stuff that I think is worth emulating by other museums.

The museum is, as the name already suggests, devoted entirely to detailing the history of Sweden, from prehistoric times up to the present day. In the cellar, you’ll find a treasure vault with lots of valuable items; if you like gold, this should be your first stop. The ground floor is dedicated to prehistoric and Viking-era Sweden. Medieval and modern history can be found up on the first floor. You’ll probably need two days to have a careful look at everything; two afternoons were not quite enough for my girlfriend and me to see everything.

In many ways, the treasure vault in the cellar is the most traditional exhibition in the museum. There are loads of display cases here filled with objects. There are some explanations on the walls that go into some further detail, such as the trade in amber. But on the whole, it’s perhaps the least impressive didactically speaking. Here’s a view of the centre chamber:

On the ground floor, I really loved the archaeology department. The main corridor is arranged like an airport lounge. There is a screen overhead that pops up questions, and if you want to find out the answer you’ll have to go to the room (‘gate’) indicated. For example: ‘How is your world organized? Go to gate A3.’ It’s a neat concept. The space allows for visitors to have a seat and contemplate matters, look at the screen, and then decide where to go to next.

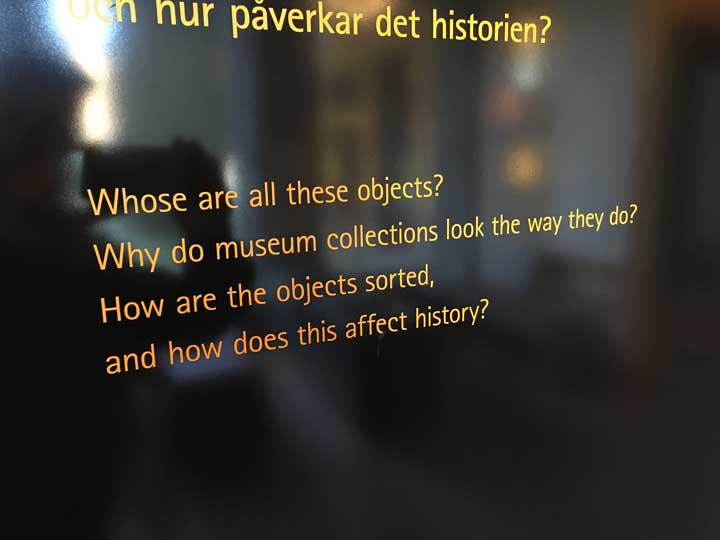

The different rooms each focus on one or more questions. The exhibits inside the rooms generally don’t answer these questions, but try to force the visitor to think critically about things. For example, one room features these questions at the door:

The different rooms each focus on one or more questions. The exhibits inside the rooms generally don’t answer these questions, but try to force the visitor to think critically about things. For example, one room features these questions at the door:

These are all very practical questions, but I’ve never actually seen a museum come out and confront the visitor with them. ‘Whose are all these objects?’ Do they belong to the museum? To the government? Should they belong to you and me? ‘Why do museum collections look the way they do?’ What choices did the staff make? Who is the staff? And why do they get to make the decisions? And so forth. These are interesting questions that go direct to the heart of the matter: whose past is it?

These are all very practical questions, but I’ve never actually seen a museum come out and confront the visitor with them. ‘Whose are all these objects?’ Do they belong to the museum? To the government? Should they belong to you and me? ‘Why do museum collections look the way they do?’ What choices did the staff make? Who is the staff? And why do they get to make the decisions? And so forth. These are interesting questions that go direct to the heart of the matter: whose past is it?

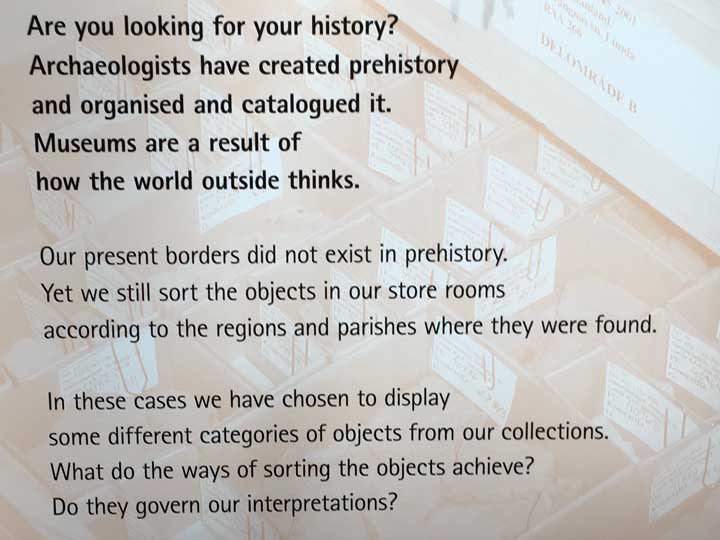

In this room, one text immediately makes clear that prehistory is, in fact, created:

Archaeologists love nothing better than to organize objects, classifying them according to type and arranging them in chronological order. The big display cases in this room give a number of examples, such as these axes:

Archaeologists love nothing better than to organize objects, classifying them according to type and arranging them in chronological order. The big display cases in this room give a number of examples, such as these axes:

And then do the exact same thing with modern brushes and brooms, to show how you can organize stuff. It also demonstrates that this exercise is, in many ways, deeply subjective:

And then do the exact same thing with modern brushes and brooms, to show how you can organize stuff. It also demonstrates that this exercise is, in many ways, deeply subjective:

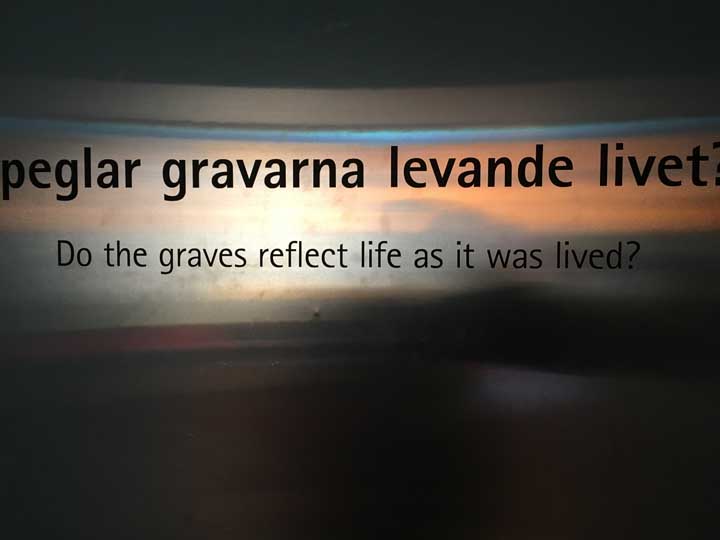

Another great example of how the Swedish History Museum forces their visitors to think critically is this sign in another room in the prehistoric department:

Another great example of how the Swedish History Museum forces their visitors to think critically is this sign in another room in the prehistoric department:

Indeed, do graves reflect life as it was lived? It’s a fundamental question in archaeology, but one that is hardly ever tackled head on. The room in which this question is posed actually features a number of exhibits in which the relationship between objects and everyday life are questioned, including a display featuring a bathroom cabinet. Visitors are invited to have a look and determine the number of people living in that particular house and what their genders might be. It’s a simple but effective way to get people to think about these kinds of issues.

Indeed, do graves reflect life as it was lived? It’s a fundamental question in archaeology, but one that is hardly ever tackled head on. The room in which this question is posed actually features a number of exhibits in which the relationship between objects and everyday life are questioned, including a display featuring a bathroom cabinet. Visitors are invited to have a look and determine the number of people living in that particular house and what their genders might be. It’s a simple but effective way to get people to think about these kinds of issues.

Moving along, the Viking exhibition on the ground floor is also interesting, but a tad more traditional. There were a few areas where some reconstructions were made that were insightful, such as part of a Viking-era house. Furthermore, we were fortunate that there was a kind of living history display in the courtyard where, among other things, you could try your hand at shooting a low-powered bow. Unfortunately, since we were rather late in the afternoon on the days we visited, most of the reenactors had already left.

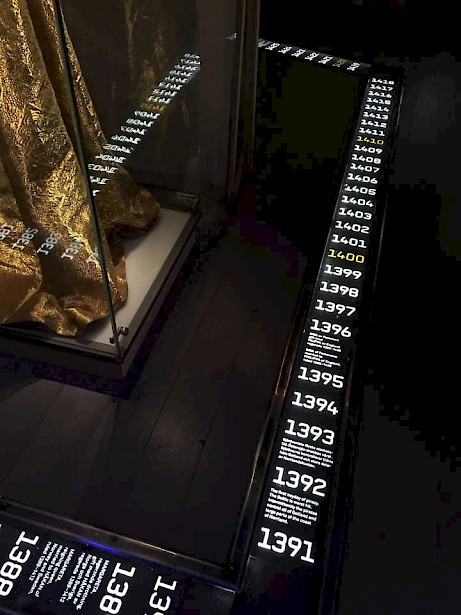

The upper floor featured rooms that were organized more or less chronologically. The displays were all interesting, but one feature I loved in particular was a timeline that the creators had embedded into the floor. Here’s a picture of part of this timeline:

The focal point for the room in question is highlighted in yellow (in the photo above, the year 1400). Major events are briefly described as well (here, as elsewhere, in both Swedish and English), as you can see for the years 1396, 1393, and others in the photo above. It’s a very simple way to show the passage of time, and as you move from room to room, you can always get idea of when you are by simply looking down at the floor.

The focal point for the room in question is highlighted in yellow (in the photo above, the year 1400). Major events are briefly described as well (here, as elsewhere, in both Swedish and English), as you can see for the years 1396, 1393, and others in the photo above. It’s a very simple way to show the passage of time, and as you move from room to room, you can always get idea of when you are by simply looking down at the floor.

I could go on and on, but you should really visit the museum for yourself. The collection itself is comprehensive, but the way that the museum presents information is simply fantastic. And Stockholm is a great city to wander round in, so if you’re still undecided as to a holiday destination, I recommend that you check out Sweden!