Why Hastings was an unusual battle

“Then began death-bearing clouds of arrows. There followed the thunder of blows. The clash of helmets and swords produced dancing sparks.” ~ Henry of Huntingdon, describing the Battle of Hastings

Throughout Great Britain they are marking the 950th anniversary of the Battle of Hastings, perhaps the single most important day of fighting that took place on English soil. Historians have long debated every aspect of the battle between the Anglo-Saxon king Harold Godwinson and William, Duke of Normandy. One of the most important contributions to this topic comes from Stephen Morillo.

Morillio’s article “Hastings: An Unusual Battle” was first published in 1990 as part of The Haskins Society Journal. He advises his readers that “special care in interpretation” when it comes to looking at the battle fought on October 14, 1066, because it was highly unusual in three important ways:

1) It was unusually long

Accounts about the battle note that it took place over a nine-hour period, whereas the typical medieval battled rarely lasted more than two hours. Morillo adds that “it is hard to find a longer battle until well into the age of gunpowder.”

2) The two sides were evenly matched

The fighting at Hastings saw both sides attacking and counterattacking, with multiple attempts by the Normans to break the English line. In most medieval battles, one side has a distinct advantage that allowed them a quick victory.

3) The results were decisive

Even when one side wins a battle, their opponents are able to fight again another day. Kings rarely fall on the battlefield, but instead retreat with their forces. At Hastings not only was King Harold killed, but much of the Anglo-Saxon elite as well. It would usher in a brand new ruling dynasty over England, changing the course of history for the English.

Morillo notes that previous historians have been quick to say that the Norman style of warfare, with the use of cavalry and charges, was superior to the infantry-based Anglo-Saxon army. These historians believed that William’s victory was a foregone conclusion, an assertion that he rejects:

On a level of analysis specific to Hastings, such a view seems in conflict with the unusual length and difficulty of the battle noted above. One would not expect inevitable victories to take so long, to be so hard, or to be almost lost. And the dominant tactics of the day were in fact evenly matched. The English defensive formation was just the sort that would turn back charging cavalry - densely massed infantry - while the hand-to-hand combat along the line matched Norman swords and lances against Saxon battle axes which ‘easily found their way through shields or other armor,’ as William of Poitiers say, with no advantage either way.

If one military force was not better than other, then why did the Normans prevail. For Morillo the main difference was between the two commanders - William and Harold:

Leadership is crucial to how any army performs. Armies which were somewhat less than disciplined machines magnified the effects of leadership. Leadership, I believe, can account for the unusual features of the battle of Hastings.

He offers some key points from the battle for readers to consider - Duke William rallying his troops after they believed he was dead, and then luring the English forces to leave their position in a feigned retreat. Meanwhile King Harold may have stood with his army, but was unable to control them at vital moments.

In the end Morillo concludes that “given the essentially equal armies, William simply outgeneraled Harold and had bit more luck.”

This article can be found in Stephen Morillo’s book The Battle of Hastings, which was published by Boydell and Brewer in 1996. His other book Warfare under the Anglo-Norman Kings, 1066-1135, also offers insights into the battle. You can read more of Morillo’s work on his Academia.edu page.

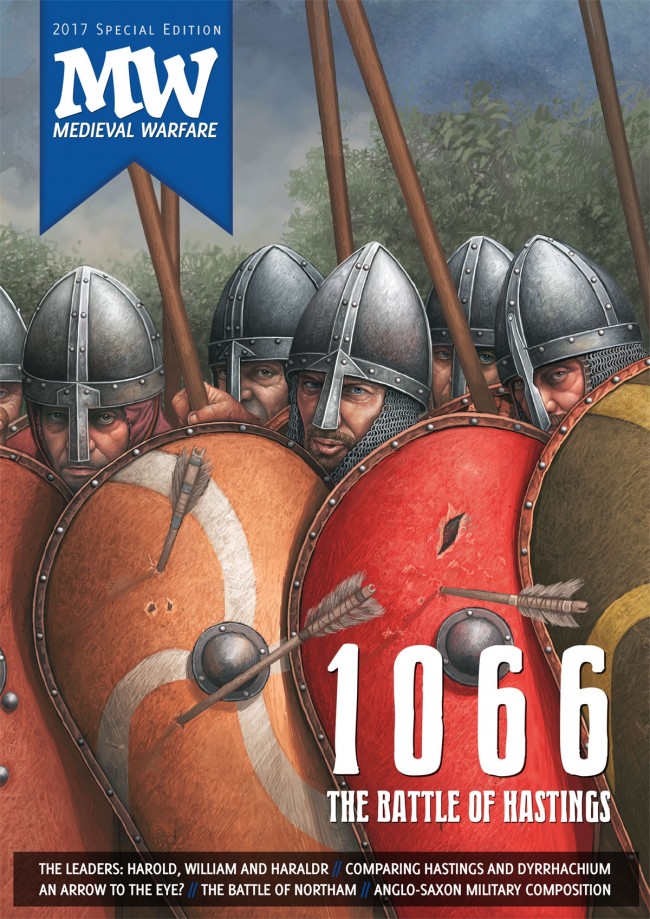

To learn more about the Battle of Hastings, take a look at our special issue of Medieval Warfare.